Postscript: This video was posted on December 24, 2024, by the Recruiting Center of the Armed Forces of Ukraine:

Art is a weapon. Do not let the song become silence.

I must confess that, while growing up in Germany, I never heard this song.

It is well-known in the English-speaking world, as one gathers from the many ways in which it has been commercialized:

Here it is sung by the Choir of St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, during a Christmas service in 2018:

And here it is performed by the Crimean Chamber Choir — though not as a Christmas carol:

The original Ukrainian song “Shchedryk” is not about Christmas but about New Year’s Eve, when a swallow flies into a house and wishes the family a happy and plentiful year ahead. “Shchedryk” comes from a Ukrainian word that means “generosity.”

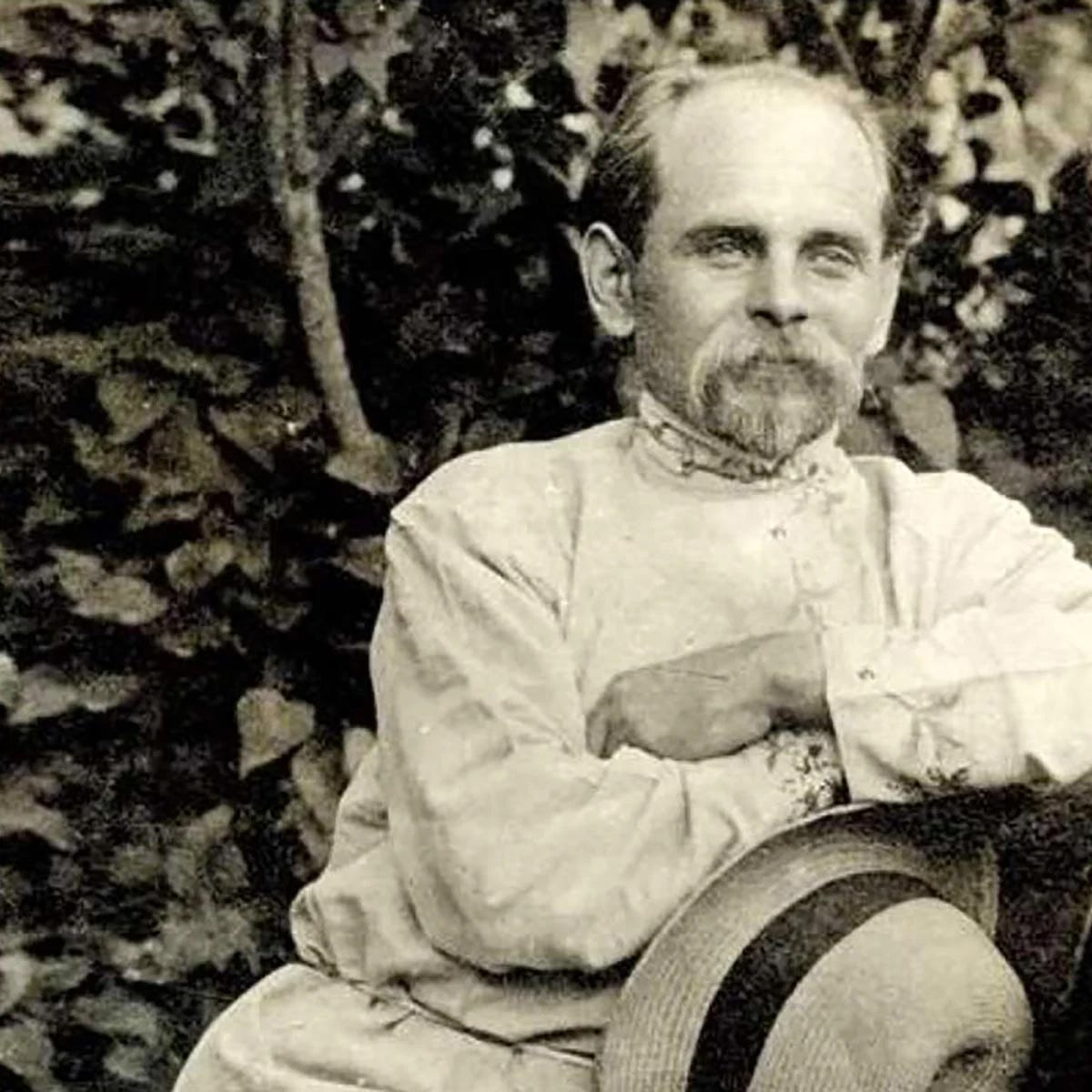

Read about Mykola Leontovych, the Ukrainian composer of the song, who took inspiration from a Ukrainian folk song dating back to pre-Christian times. What follows is adapted from this post:

Leontovych composed Shchedryk in the Eastern Ukrainian town of Pokrovsk, which at this very moment is under continuous shelling by Russian forces. Shchedryk was first performed in Kyiv in 1916.

After the revolution of 1917, the Russian empire collapsed, and the Ukrainian People’s Republic was formed. Finally, people could perform Ukrainian songs and celebrate Ukrainian culture without fear of prosecution. Months after the revolution, Russian Bolsheviks occupied the East of Ukraine, claiming that it was “a liberation” and framing their invasion as an internal Ukrainian conflict. (Clearly, there’s nothing new under the Sun.)

The Russian elite who after the revolution had fled to the West received sympathy, and they successfully promoted Russian imperial interests. They presented Ukrainians as “Malorussians” without distinct culture and history, and people believed them.

When, in 1919, Ukraine was bleeding on the frontline, outnumbered and unequipped but desperately fighting for freedom, the world was supporting Russian imperialist ambitions and admiring Russian culture. At that time, Ukrainian state commander Symon Petliura visited a concert in Kyiv where he heard a composition by Mykola Leontovych. Deeply impressed, he came up with the idea of showcasing Ukrainian culture to the world.

His idea was to bring a Ukrainian choir to Paris for the Paris Peace Conference, where the future of Ukraine was to be decided by the world’s powers. The choir was organized within a few weeks, and Oleksandr Koshyts was assigned as the head of the choir. When he asked Leontovych’s permission to include Shchedryk in the program, Leontovych refused. He couldn’t imagine that people in Prague or Paris wanted to listen to Shchedryk. Koshyts included it anyway, and it became a hit. Sadly, Mykola Leontovych never learned of his song’s success.

Two weeks after the start of the tour preparations, Russian Bolsheviks made a breakthrough and occupied Kyiv. The choir members stayed in the city until the very last moment when they were ordered to evacuate. The singers caught the last train, leaving Kyiv for Kamianets’-Podilskyi.

It was February, the train didn’t have heating, and all the windows were broken. The rails were covered in snow, and the train made frequent stops lasting for hours until the snow was removed. The journey that was supposed to take one day took almost a week, and people were starving and exhausted. Eventually they reached Kamianets’-Podilskyi, where more singers joined the choir. After months of preparation and waiting for the papers, they left for Uzhhorod (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), the first town on their tour.

When the Ukrainian choir arrived in Uzhhorod, they were put in jail. Russians had contacted the authorities and claimed that the singers were communists. Locked in cells, they were lectured by the head of the police about “the great Russian culture” and that there was no Ukraine. Eventually the choir was freed, after a call from Ukrainian officials. They gave their first concert, which was a great success.

After that, the singers went to Prague, where again the police detained them. Russians had informed the Prague authorities that the Ukrainians were smugglers bringing counterfeit money to Czechoslovakia. The police confiscated the money of the choir members without any investigation. As the singers recall in their diaries, they were met with outright hostility; at every encounter they had to try and convince people that Ukraine existed and was an independent country. The concert was held on May 11, 1919, and the Czech people immediately changed their attitude. Shchedryk became a hit that people sang in the streets.

In his review for the Hudebni Revue, Czech conductor Jaroslav Kržička wrote:

It is difficult for my hand to write criticism when the heart sings praise. The Ukrainians came and won. I think we knew very little about them and deeply offended them by unknowingly and uninformed lumped them together against their will with the Russian people. Our desire for a ‘great and indivisible Russia’ is a weak argument against the distinct nature of the Ukrainian people, for whom independence is as vital as it once was for us.

Despite multiple attempts, visas were denied by the French authorities. To them, Ukraine was an unrecognized state, and Russian emigres were using their influence to prevent Ukrainians from coming to Paris. While the Peace Conference was in full swing, the Ukrainians had no choice but to tour other European countries. After Prague, the Ukrainian choir moved to Austria where they performed eleven concerts. The Austrian press wrote that “Ukraine’s cultural maturity must become the legitimization of its political independence in the world.”

Then the choir moved to Switzerland, where again it enjoyed huge success. A correspondent for the Swiss newspaper La Patrie Suisse wrote: “The Ukrainian Republic is striving to restore its independence and decided to demonstrate that it really exists. ‘I sing therefore I exist,’ it says. And it sings amazingly.”

It seemed that the Ukrainians would never make it to France until one day the French ambassador attended a concert in Bern, Switzerland. So moved he was that he wrote to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs asking to grant visas to the choir members. In November 1919, nine months after leaving Ukraine, the choir was finally able to come to Paris. By then, the world’s leaders had already decided to divide Ukraine between Russia, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. The choir came too late.

When, on November 6, 1919, the choir performed in Paris, Russian emigres tried to disrupt the concert by booing and declaring the choir members to be enemies of France, until they were escorted away by the French police. The Paris concert, too, was a colossal success. In all, twenty-five concerts were given in France. After France, the choir performed more than hundred concerts in Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, and Poland. They were attended by heads of state, royal families, famous academics, and celebrities, and they always received the highest praise. A Brussels newspaper wrote: “Ukrainians have given us not only beauty but also a lesson in national self-awareness.” The choir was also supposed to perform in Italy, but their visas were revoked the day after they were received, due to never-ending Russian interference.

By 1921, Russian Bolsheviks completely occupied Ukraine and started to arrest and kill Ukrainian composers, musicians, writers, artists, scientists, and politicians.

In January 1921, the Ukrainian choir started a new tour in Paris. The concerts were attended by well-known composers, music critics, General Maurice Pelle, ballerina Isadora Duncan, and others. On January 23, the choir gave the final morning concert, where encores of Shchedryk were requested as usual. Little did they know that at the very same time, Mykola Leontovych was killed in his home by a Russian agent, Afanasy Hrishchenko. He came to the house the previous evening, pretending to be a lost traveler, and asked to spend the night. Leonotvych's family let him in, shared dinner with him, and went to sleep. In the morning, the family was woken up by the sound of the shot. The agent killed the author of one of the most loved songs in Europe, robbed the house, and fled.

In 1922, the Soviet Union was formed, which swallowed not only Ukraine but most neighboring countries. The members of the choir, who didn’t have a country to return to anymore, left for the United States. Only one person later came back to Soviet-occupied Ukraine, was immediately arrested, and shot. All the other singers never returned home and had no contact with their families.

The Ukrainian choir gave its first concert in the U.S. on October 5, 1922, at Carnegie Hall, New York. The choir toured across the U.S. and received standing ovations everywhere they performed. Unfortunately, the person who organized the concerts being an immigrant from the Russian Empire and enamored of “the great Russian culture,” added Russian singers to the program. As they relied on him and his help, the Ukrainians had no choice. Because of that, many American newspapers started calling the Ukrainian choir “a Russian choir” and labelling Shchedryk “a Russian folk song.” They also called Mykola Leontovych “a Russian composer,” even though Russians killed him for being a Ukrainian. Soon Russians sang Ukrainian songs to Americans and told them that they were Russian songs.

Listen to the first recording of Shchedryk made in New York City in October of 1922 on the Brunswick label.

From 1923 to 1924, the Ukrainian choir performed in 115 cities in 36 states of the U.S., as well as in Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay, and Cuba.

In 1936, an American conductor of Ukrainian descent, Peter Wilhousky, wrote the English lyrics thereby creating “Carol of the Bells.” The song played on NBC and instantly became a hit. Since then, it has been featured in popular movies and commercials and has become one of the world’s most famous Christmas songs.

All the while, Ukrainians, having been isolated from the free world by 70 years of Soviet dictatorship, had no idea that the entire world sang a Ukrainian song every Christmas. They found out only in the 90s, when the Soviet Union collapsed, and Ukrainians watched “Home Alone.” That’s how Shchedryk came back to Ukraine. When the archives were unlocked, Ukrainians learned about Mykola Leontovych and how the Ukrainian choir went on a mission to save their country by sharing Ukrainian culture with the world.

Right now, Pokrovsk, the town where Shchedryk was written, is being encircled and bombarded by Russians. After more than 100 years, Ukraine’s struggle for independence continues. The bloodthirstiness of Russians and the willful blindness of the Western world haven’t changed either. Ukrainians still have to prove that they exist and are worthy of freedom.

Many thanks to Darya Zorka for this recent post, from which the above text has been adapted.

And above all, the most heartfelt thanks to Ukraine:

On December 4, 2022, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the premiere of Shchedryk at Carnegie Hall, New York, it was again performed there:

it is very typical for russians to steal the best from other people and kill them. the whole russian culture is made of these thefts. no wonder that the ideal for russia is a 'thief in law' title of the highest rank of a criminal world.

🤔 Ukraine approves homemade Shchedryk aerial vehicle for military use:

https://kyivindependent.com/ukraine-approves-homemade-shchedryk-aerial-vehicle-for-military-use/