The malady of the world

The radical defect of all our systems is their deficient development of just that which society has most neglected

Timothy Snyder is professor of history at Yale and a leading authority on authoritarianism and the history of Eastern Europe. I have nothing but the deepest respect for his scholarship and his clearsighted assessment of what is at stake during the current political crisis. If, therefore, I appear to be critical in what follows of something he wrote, it is not to criticize him personally but to point out how far our most reputable public intellectuals are from discerning the true solution to what is ailing humanity, and therefore how far we — human society —remain from arriving at the solution.

Snyder recently published Our Malady: Lessons in Liberty from a Hospital Diary (Crown 2020). This slender volume builds on reflections, penned during a long hospital stay, on America’s malady of “physical illness and the political evil that surrounds it.” As necessary as are the cures he suggests, they don’t seem to be attainable unless and until the true malady is recognized and addressed.

“I raged, therefore I was,” Snyder recalls. This rage “was not against anything, except the entire universe and its laws of unlife.” Whoever cannot — especially at this particular juncture in time — relate to this rage, has either rocks in his head or a stone for a heart. Our Malady contains this eerily prescient reminder:

History remembers the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain unkindly because he told his people what they wanted to hear in 1938: that there need be no war. History remembers Winston Churchill kindly because he told the British what they needed to hear: that Hitler had to be stopped.

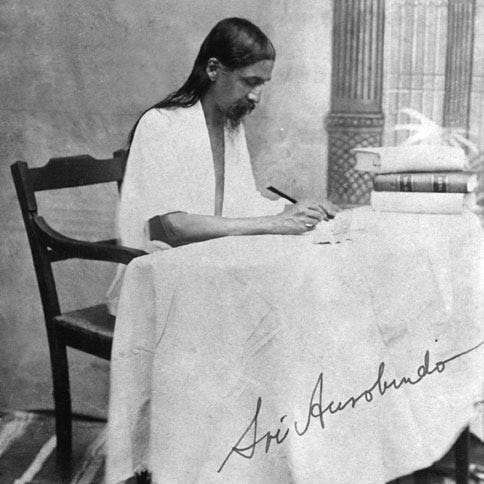

After the rage, a gentler mood: “Yet, slowly and softly, a second mood impinged, one that sustained me in a different way: a feeling that life was only truly life insofar as it was not only about me.” This points in the right direction, but it doesn’t go far enough. It identifies the problem — the little separative “me” — but not the solution, which is that ultimately there is but a single universal Me. In the words of Sri Aurobindo:

The malady of the world is that the individual cannot find his real soul, and the root-cause of this malady is again that he cannot meet in his embrace of things outward the real soul of the world in which he lives. He seeks to find there the essence of being, the essence of power, the essence of conscious-existence, the essence of delight, but receives instead a crowd of contradictory touches and impressions. If he could find that essence, he would find also the one universal being, power, conscious existence and delight even in this throng of touches and impressions; the contradictions of what seems would be reconciled in the unity and harmony of the Truth that reaches out to us in these contacts. At the same time he would find his own true soul and through it his self, because the true soul is his self’s delegate and his self and the self of the world are one. [LD 234–235]

Snyder observes that “[t]o be free is to become ourselves, to move through the world following our values and desires.” The first part is entirely correct, provided that to become ourselves is to become our true self one with the self of the world. As we have seen here, there is but one way to be truly free, and that is to be consciously and effectively one with the ultimate and sole determinant of the world. Following our values is also right, provided that what is meant are the values of our true self, for only these are in harmony with the Truth that reaches out to us through our contacts with the world. But desires? “Desire” usually refers to the cravings of the little separative “me,” which are rarely in harmony even with each other, let alone with those of the other little “mes.”

There is no denying that “[e]ach of us has a right to pursue happiness,” as long as my happiness isn’t the cause of your unhappiness, which it typically is if the happiness in question is that pursued by the little separative “me.” True happiness is the prerogative of the universal Me. The right pursuit of happiness is that which will ultimately lead to oneness with that Me and the realization of its self-existent, unconditional delight of being.

Snyder seconds Gandalf the wizard: “without knowledge freedom has no chance.” While rational knowledge, based on how things appear to the little “me,” may be necessary for relieving the little “me” of some of its ailments — though it may also make them worse — it is certainly not sufficient for attaining genuine freedom. What is axiomatic is that true knowledge, which is suprarational and based on how things really are (i.e., how they “appear” to the universal Me), implies true freedom, and vice versa.

Because “[w]e see our malady all too vaguely,” Snyder invokes a motto of the Enlightenment: “dare to know.” To see our malady more clearly, we must dare to know its true origin, initially by knowing it intellectually — and for this there appears to be no better guide than the writings of Sri Aurobindo — and eventually by acquiring the knowledge and concomitant power to cure it.

The following passages are excerpts from the last three chapters of Sri Aurobindo’s The Human Cycle. The twenty-four chapters making up this work appeared in the Arya under the title The Psychology of Social Development between August 1916 and July 1918. During the 1930s, probably around 1937, Sri Aurobindo revised the Arya text twice. The revised text remained unpublished until 1949, at which time Sri Aurobindo dictated minor changes in the final revision. Here goes.

Nietzsche’s idea that to develop the superman out of our present very unsatisfactory manhood is our real business, is in itself an absolutely sound teaching. His formulation of our aim, “to become ourselves”, “to exceed ourselves”, implying, as it does, that man has not yet found all his true self, his true nature by which he can successfully and spontaneously live, could not be bettered. But then the question of questions is there, what is our self, and what is our real nature? What is that which is growing in us, but into which we have not yet grown?... Is it the intellect and will...? But this is at present a thing so perplexed, so divided against itself, so uncertain of everything it gains, up to a certain point indeed magically creative and efficient but, when all has been said and done, in the end so splendidly futile, so at war with and yet so dependent upon and subservient to our lower nature, that even if in it there lies concealed some seed of the entire divinity, it can hardly itself be the seed and at any rate gives us no such secure and divine poise as we are seeking....

[A]t first sight man seems to be a double nature, an animal nature of the vital and physical being which lives according to its instincts, impulses, desires, its automatic orientation and method, and with that a half-divine nature of the self-conscious intellectual, ethical, aesthetic, intelligently emotional, intelligently dynamic being who is capable of finding and understanding the law of his own action and consciously using and bettering it, a reflecting mind that understands Nature, a will that uses, elevates, perfects Nature, a sense that intelligently enjoys Nature. The aim of the animal part of us is to increase vital possession and enjoyment; the aim of the semi-divine part of us is also to grow, possess and enjoy, but ... to possess and enjoy ... things intellectual, ethical and aesthetic, and to grow not so much in the outward life, except in so far as that is necessary to the security, ease and dignity of our human existence, but in the true, the good and the beautiful....

This means that man has developed a new power of being,—let us call it a new soul-power, with the premiss that we regard the life and the body also as a soul-power,—and the being who has done that is under an inherent obligation not only to look at the world and revalue all in it from this new elevation, but to compel his whole nature to obey this power and in a way reshape itself in its mould, and even to reshape, so far as he can, his environmental life into some image of this greater truth and law.... Failing in this, he fails in the aim of his nature and his being, and has to begin again until he finds the right path and arrives at a successful turning-point, a decisive crisis of transformation.

Now this is precisely what man has failed to do. He has effected something, he has passed a certain stage of his journey. He has laid some yoke of the intellectual, ethical, aesthetic rule on his vital and physical parts and made it impossible for himself to be content with or really to be the mere human animal. But more he has not been able to do successfully. The transformation of his life into the image of the true, the good and the beautiful seems as far off as ever; if ever he comes near to some imperfect form of it, ...he slides back from it in a general decay of his life, or else stumbles on from it into some bewildering upheaval out of which he comes with new gains indeed but also with serious losses....

The main failure, the root of the whole failure indeed, is that he has not been able to shift upward what we have called the implicit will central to his life.... The higher life is still only a thing superimposed on the lower, a permanent intruder upon our normal existence. The intruder interferes constantly with the normal life, scolds, encourages, discourages, lectures, manipulates, readjusts, lifts up only to let fall, but has no power to transform, alchemise, re-create.... All the uneasiness, dissatisfaction, disillusionment, weariness, melancholy, pessimism of the human mind comes from man’s practical failure to solve the riddle and the difficulty of his double nature....

As it is possible to superimpose the intellectual, ethical or aesthetic life or the sum of their motives upon the vital and physical nature, to be satisfied with a partial domination or a compromise, so it is possible to superimpose the spiritual life or some figure of strength or ascendency of spiritual ideas and motives on the mental, vital and physical nature and either to impoverish the latter, to impoverish the vital and physical existence and even to depress the mental as well in order to give the spiritual an easier domination.... This is the most that human society has ever done in the past, and though necessarily that must be a stage of the journey, to rest there is to miss the heart of the matter, the one thing needful. Not a humanity leading its ordinary life, what is now its normal round, touched by spiritual influences, but a humanity aspiring whole-heartedly to a law that is now abnormal to it, ...is the steep way that lies before man towards his perfection and the transformation that it has to achieve.

The secret of the transformation lies in the transference of our centre of living to a higher consciousness and in a change of our main power of living. This will be a leap or an ascent even more momentous than that which Nature must at one time have made from the vital mind of the animal to the thinking mind still imperfect in our human intelligence....

The main power of our living must be no longer the inferior vital urge of Nature which is already accomplished in us, ...but that spiritual force of which we sometimes hear and speak but have not yet its inmost secret. For that is still retired in our depths and waits for our transcendence of the ego and the discovery of the true individual in whose universality we shall be united with all others. To transfer from the vital being, the instrumental reality in us, to the spirit, the central reality, to elevate to that height our will to be and our power of living is the secret which our nature is seeking to discover. All that we have done hitherto is some half-successful effort to transfer this will and power to the mental plane; our highest endeavour and labour has been to become the mental being and to live in the strength of the idea. But the mental idea in us is always intermediary and instrumental; always it depends on something other than it for its ground of action and therefore although it can follow for a time after its own separate satisfaction, it cannot rest for ever satisfied with that alone. It must either gravitate downwards and outwards towards the vital and physical life or it must elevate itself inwards and upwards towards the spirit.

And that must be why in thought, in art, in conduct, in life we are always divided between two tendencies, one idealistic, the other realistic.... Our idealism is always the most rightly human thing in us, but as a mental idealism it is a thing ineffective. To be effective it has to convert itself into a spiritual realism which shall lay its hands on the higher reality of the spirit and take up for it this lower reality of our sensational, vital and physical nature....

[T]he perfection of man cannot consist in pursuing the unillumined round of the physical life. Neither can it be found in the wider rounds of the mental being; for that also is instrumental and tends towards something else beyond it, something whose power indeed works in it, but whose larger truth is superconscient to its present intelligence.... Man’s true freedom and perfection will come when the spirit within bursts through the forms of mind and life and, winging above to its own gnostic fiery height of ether, turns upon them from that light and flame to seize them and transform into its own image....

Man’s road to spiritual supermanhood will be open when he declares boldly that all he has yet developed, including the intellect of which he is so rightly and yet so vainly proud, are now no longer sufficient for him, and that to uncase, discover, set free this greater Light within shall be henceforward his pervading preoccupation....

A change of this kind, the change from the mental and vital to the spiritual order of life, must necessarily be accomplished in the individual and in a great number of individuals before it can lay any effective hold upon the community.... Therefore if the spiritual change of which we have been speaking is to be effected, it must unite two conditions which have to be simultaneously satisfied but are most difficult to bring together. There must be the individual and the individuals who are able to see, to develop, to re-create themselves in the image of the Spirit and to communicate both their idea and its power to the mass. And there must be at the same time a mass, a society, a communal mind or at the least the constituents of a group-body, the possibility of a group-soul which is capable of receiving and effectively assimilating....

What then will be that state of society, what that readiness of the common mind of man which will be most favourable to this change, so that even if it cannot at once effectuate itself, it may at least make for its ways a more decisive preparation than has been hitherto possible? For that seems the most important element, since it is that, it is the unpreparedness, the unfitness of the society or of the common mind of man which is always the chief stumbling-block. It is the readiness of this common mind which is of the first importance; for even if the condition of society and the principle and rule that govern society are opposed to the spiritual change, even if these belong almost wholly to the vital, to the external, the economic, the mechanical order, as is certainly the way at present with human masses, yet if the common human mind has begun to admit the ideas proper to the higher order that is in the end to be, and the heart of man has begun to be stirred by aspirations born of these ideas, then there is a hope of some advance in the not distant future. And here the first essential sign must be the growth of the subjective idea of life,—the idea of the soul, the inner being, its powers, its possibilities, its growth, its expression and the creation of a true, beautiful and helpful environment for it as the one thing of first and last importance....

A subjective age may stop very far short of spirituality; for the subjective turn is only a first condition, not the thing itself, not the end of the matter.... After the material formula which governed the greater part of the nineteenth century had burdened man with the heaviest servitude to the machinery of the outer material life that he has ever yet been called upon to bear, the first attempt to break through, to get to the living reality in things and away from the mechanical idea of life and living and society, landed us in that surface vitalism which had already begun to govern thought before the two formulas inextricably locked together lit up and flung themselves on the lurid pyre of the [first] world-war....

The Life-power is an instrument, not an aim; it is in the upward scale the first great subjective supraphysical instrument of the Spirit and the base of all action and endeavour. But a Life-power that sees nothing beyond itself, nothing to be served except its own organised demands and impulses, ...can only add the uncontrollable impetus of a high-crested or broad-based Titanism. Or it may be even a nether flaming demonism, to the Nature forces of the material world with the intellect as its servant, an impetus of measureless unresting creation, appropriation, expansion which will end in something violent, huge and “colossal”, foredoomed in its very nature to excess and ruin, because light is not in it nor the soul’s truth....

But beyond the subjectivism of the vital self there is the possibility of a mental subjectivism which would at first perhaps, emerging out of the predominant vitalism and leaning upon the already realised idea of the soul as a soul of Life in action but correcting it, appear as a highly mentalised pragmatism. This first stage is foreshadowed in an increasing tendency to rationalise entirely man and his life.... This attempt is bound to fail because reason and rationality are not the whole of man or of life, because reason is only an intermediate interpreter, not the original knower....

But it is conceivable that this tendency may hereafter rise to the higher idea of man as a mental being, a soul in mind that must develop itself individually and collectively in the life and body through the play of an ever-expanding mental existence. This greater idea would realise that the elevation of the human existence will come not through material efficiency alone or the complex play of his vital and dynamic powers, not solely by mastering through the aid of the intellect the energies of physical Nature for the satisfaction of the life-instincts, ...but through the greatening of his mental and psychic being and a discovery, bringing forward and organisation of his subliminal nature and its forces, the utilisation of a larger mind and a larger life waiting for discovery within us....

The true secret can only be discovered if in the third stage, in an age of mental subjectivism, the idea becomes strong of the mind itself as no more than a secondary power of the Spirit’s working and of the Spirit as the great Eternal, the original and, in spite of the many terms in which it is both expressed and hidden, the sole reality....

[T]he way that humanity deals with an ideal is to be satisfied with it as an aspiration which is for the most part left only as an aspiration, accepted only as a partial influence. The ideal is not allowed to mould the whole life, but only more or less to colour it; it is often used even as a cover and a plea for things that are diametrically opposed to its real spirit. Institutions are created which are supposed, but too lightly supposed to embody that spirit and the fact that the ideal is held, the fact that men live under its institutions is treated as sufficient. The holding of an ideal becomes almost an excuse for not living according to the ideal; the existence of its institutions is sufficient to abrogate the need of insisting on the spirit that made the institutions. But spirituality is in its very nature a thing subjective and not mechanical; it is nothing if it is not lived inwardly and if the outward life does not flow out of this inward living....

A society that lives not by its men but by its institutions, is not a collective soul, but a machine; its life becomes a mechanical product and ceases to be a living growth. Therefore the coming of a spiritual age must be preceded by the appearance of an increasing number of individuals who are no longer satisfied with the normal intellectual, vital and physical existence of man, but perceive that a greater evolution is the real goal of humanity and attempt to effect it in themselves, to lead others to it and to make it the recognised goal of the race....

A great access of spirituality in the past has ordinarily had for its result the coming of a new religion of a special type and its endeavour to impose itself upon mankind as a new universal order. This, however, was always not only a premature but a wrong crystallisation which prevented rather than helped any deep and serious achievement.... A religious movement brings usually a wave of spiritual excitement and aspiration that communicates itself to a large number of individuals and there is as a result a temporary uplifting and an effective formation, partly spiritual, partly ethical, partly dogmatic in its nature. But the wave after a generation or two or at most a few generations begins to subside; the formation remains. If there has been a very powerful movement with a great spiritual personality as its source, it may leave behind a central influence and an inner discipline which may well be the starting-point of fresh waves; but these will be constantly less powerful and enduring in proportion as the movement gets farther and farther away from its source. For meanwhile in order to bind together the faithful and at the same time to mark them off from the unregenerated outer world, there will have grown up a religious order, a Church, a hierarchy, a fixed and unprogressive type of ethical living, a set of crystallised dogmas, ostentatious ceremonials, sanctified superstitions, an elaborate machinery for the salvation of mankind....

The ambition of a particular religious belief and form to universalise and impose itself is contrary to the variety of human nature and to at least one essential character of the Spirit. For the nature of the Spirit is a spacious inner freedom and a large unity into which each man must be allowed to grow according to his own nature. Again—and this is yet another source of inevitable failure—the usual tendency of these credal religions is to turn towards an afterworld and to make the regeneration of the earthly life a secondary motive.... The ascent of man into heaven is not the key, but rather his ascent here into the spirit and the descent also of the spirit into his normal humanity and the transformation of this earthly nature. For that and not some post mortem salvation is the real new birth for which humanity waits as the crowning movement of its long obscure and painful course.

Therefore the individuals who will most help the future of humanity in the new age will be those who will recognise a spiritual evolution as the destiny and therefore the great need of the human being.... They will be comparatively indifferent to particular belief and form and leave men to resort to the beliefs and forms to which they are naturally drawn. They will only hold as essential the faith in this spiritual conversion, the attempt to live it out and whatever knowledge—the form of opinion into which it is thrown does not so much matter—can be converted into this living.... They will not accept the theory that the many must necessarily remain for ever on the lower ranges of life and only a few climb into the free air and the light, but will start from the standpoint of the great spirits who have striven to regenerate the life of the earth and held that faith in spite of all previous failure. Failures must be originally numerous in everything great and difficult, but the time comes when the experience of past failures can be profitably used and the gate that so long resisted opens. In this as in all great human aspirations and endeavours, an a priori declaration of impossibility is a sign of ignorance and weakness....

This endeavour will be a supreme and difficult labour even for the individual, but much more for the race. It may well be that, once started, it may not advance rapidly even to its first decisive stage; it may be that it will take long centuries of effort to come into some kind of permanent birth. But that is not altogether inevitable, for the principle of such changes in Nature seems to be a long obscure preparation followed by a swift gathering up and precipitation of the elements into the new birth, a rapid conversion, a transformation that in its luminous moment figures like a miracle.

Even when the first decisive change is reached, it is certain that all humanity will not be able to rise to that level. There cannot fail to be a division into those who are able to live on the spiritual level and those who are only able to live in the light that descends from it into the mental level. And below these too there might still be a great mass influenced from above but not yet ready for the light. But even that would be a transformation and a beginning far beyond anything yet attained. This hierarchy would not mean as in our present vital living an egoistic domination of the undeveloped by the more developed, but a guidance of the younger by the elder brothers of the race and a constant working to lift them up to a greater spiritual level and wider horizons. And for the leaders too this ascent to the first spiritual levels would not be the end of the divine march, a culmination that left nothing more to be achieved on earth.

I’ve come to appreciate every word he says, enormously. And it never stops surprising me, his broad insight, his deep understanding of historical forces. What he said about a future subjective age, and the vitalism before WWI is extraordinary. It reverberates with so many ideas buried in the past. Not to mention this passage:

“A society that lives not by its men but by its institutions, is not a collective soul, but a machine.”

In relation to that, the failure he refers to at the beginning of the text is only partially man’s own making. The “megamachine”, the “mechanical order”, that humanity perfected long time ago and put into motion acquired a soul of its own. When people talk about some dystopian future inhabited by automated organisms, or the abhorred enslavement of the masses exerted by some primitive megalomaniac king, as if they were two extremes on a distant and impossible line: we are that future already, we have always been that past.

“To understand the point of the machine's origin and its line of descent is to have a fresh insight into both the origins of our present over mechanized culture and the fate and destiny of modern man. We shall find that the original myth of the machine projected the extravagant hopes and wishes that have come to abundant fulfillment in our own age. Yet at the same time it imposed restrictions, abstentions, and compulsions and servilities that, both directly and as a result of the counter-reactions they produced, today threaten even more mischievous consequences than they did in the Pyramid Age. We shall see, finally, that from the outset all the blessings of mechanized production have been undermined by the process of mass destruction which the megamachine made possible.” (Lewis Mumford, The Myth of the Machine, Vol. I, 9, p.189. 1962)

Everything that is, is as object. I have only two objections against this, the most extraordinary of modern views: You are not an object, you are all that is.