In the philosophy of mind there are two competing schools: externalism and internalism. Externalism makes the distinction between (i) representations (such as theories and beliefs) and (ii) the world being represented, the world that the beliefs are about, the world that the theories are intended to model or describe. This distinction creates an unbridgeable chasm. While our representations purport to match the external world, we are in no position to effect a comparison. The best we can do is draw comparisons between different representations.

Externalism thus opens the door to skepticism about the external world. What grounds do we have for thinking that our representations or beliefs are true or correct? As the Greek philosopher-poet Xenophanes pointed out some twenty-five centuries ago,1 “certain truth [about God or the world] has not and cannot be attained by any man; for even if he should fully succeed in saying what is true, he himself could not know that it was so.” If we have access only to representations, then we can have no assurance that our representations match the reality they purport to represent, or even whether there is such a reality.

The first philosopher who did not think of truth as a correspondence between things in themselves and their mental representation was, arguably, Immanuel Kant. Even Bishop Berkeley based truth of knowledge on such a correspondence (with God’s ideas taking the place of things in themselves), nor did David Hume deny the existence of a mind-independent reality; he only denied the possibility of knowing how it relates to our thoughts and perceptions. And even Kant, though he gave a wholly new meaning to “truth,” still did not abandon the idea of an empirically unknowable thing in itself. Here is how the philosopher Hilary Putnam2 paraphrased Kant’s meaning of “truth”:

[A] piece of knowledge (i.e. a “true statement”) is a statement that a rational being would accept on sufficient experience of the kind that it is actually possible for beings with our nature to have. “Truth” in any other sense is inaccessible to us and inconceivable by us. Truth is ultimate goodness of fit.

Goodness of fit contrasts with goodness of match, the latter being what a cartographer strives for. The substitution of the concept of fit for the traditional concept of truth as a matching, isomorphic, or iconic representation of reality, is at the heart of the theory of knowledge developed by Ernst von Glasersfeld,3 which is known as “radical constructivism”.4 A key fits a lock if it opens it. “Fit” describes a capacity of the key, not a feature of the lock. As professional burglars know only too well, there are many keys that are shaped quite differently from ours but nevertheless unlock our doors.5 “From the radical constructivist point of view,” von Glasersfeld observed, “all of us — scientists, philosophers, laymen, school children, animals, indeed any kind of living organism — face our environment as the burglar faces a lock that he has to unlock in order to get at the loot.”

In the introduction to a seminal collection of essays on radical constructivism, Paul Watzlawick6 offered the following analogy:

A captain who on a dark, stormy night has to sail through an uncharted channel, devoid of beacons and other navigational aids, will either wreck his ship on the cliffs or regain the safe, open sea beyond the strait. If he loses ship and life, his failure proves that the course he steered was not the right one. One may say that he discovered what the passage was not. If, on the other hand, he clears the strait, this success merely proves that he literally did not at any point come into collision with the (otherwise unknown) shape and nature of the waterway; it tells him nothing about how safe or how close to disaster he was at any given moment. He passed the strait like a blind man. His course fits the unknown topography, but this does not mean that it matched it — if we take matching in von Glasersfeld’s sense, that is, that the course matched the real configuration of the channel.

Yet even the concept of knowledge as fitting an unknown environment presupposes an environment. Even the sceptic who argues that we are or may be deceived by our thoughts or senses, takes for granted the possibility of not being deceived. As John Austin7 has pointed out, “talk of deception only makes sense against a background of general non-deception”:

It must be possible to recognize a case of deception by checking the odd case against more normal ones. If I say, “Our petrol-gauge sometimes deceives us,” I am understood: though usually what it indicates squares with what we have in the tank, sometimes it doesn’t — it sometimes points to two gallons when the tank turns out to be nearly empty. But suppose I say, “Our crystal ball sometimes deceives us”: this is puzzling, because really we haven’t the least idea what the “normal” case — not being deceived by our crystal ball — would actually be.

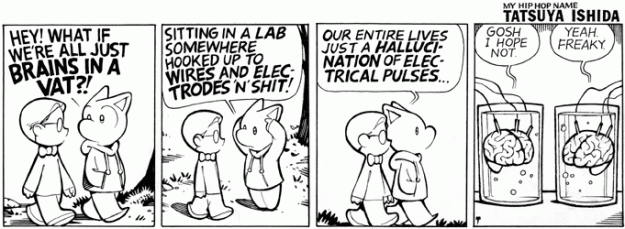

Brains in vats

Over the years, Hilary Putnam has come up with several ways to refute externalism. Putnam had a penchant for changing his views, even completely reversing himself on central themes, which has earned him the following entry in The Philosophical Lexicon8:

hilary, n. (from hilary term) A very brief but significant period in the intellectual career of a distinguished philosopher. “Oh, that’s what I thought three or four hilaries ago.”

This reminds me of Waldo Emerson’s famous but often misquoted statement9: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do.”

Putnam has updated the skeptical challenge by asking what grounds we have for believing that we aren’t brains in vats. Imagine that your visual and auditory experiences, as well as the kinesthetic feedback you receive when you seem to move your body, are fed to you by a computer. And imagine that we are all in the same position, and have always been, so that when I seem to myself to be talking to you, you seem to yourself to be hearing my words.

Let’s note, to begin with, that such a scenario is possible only so long as we accept externalism and its attendant gap between how the world is and how we represent it as being or how it appears to us. For otherwise we could not entertain the possibility of being so radically deceived about what we really are when in reality we are brains in vats. The supposition that there could be a world in which all sentient beings are brains in vats presupposes from the outset a God’s Eye view of truth, or, more accurately, a view of truth as independent of observers altogether.

Because the objects we experience (including brains, vats, and computers) are made of atoms and molecules, the meaning of “brain” is equivalent to “brain made of atoms and molecules,” the meaning of “vat” is equivalent to “vat made of atoms and molecules,” and so on. If, on the other hand, I utter the sentence “I am a brain in a vat,” I imply that I inhabit a computer-generated reality, in which case the meaning of “brain” is equivalent to “brain generated by a computer,” the meaning of “vat” is equivalent to “vat generated by a computer,” and so on. These are two different languages. The language we actually use is based on our experiences, from which we infer that brains, vats, and computers are made of atoms and molecules. We don’t speak the language in which brains and vats are computer-generated, nor do we know what “brain” and “vat” could mean in this language. The computers we know are the computers we know from experience. When I say that I live in a computer-generated reality, the word “computer” refers to an external reality inaccessible to me, in which case I have no idea of what it could mean or what I am talking about.

The conclusion Putnam draws from this line of reasoning is that “the supposition that we are actually brains in a vat, although it violates no physical law, and is perfectly consistent with everything we have experienced, cannot possibly be true. It cannot possibly be true, because it is, in a certain way, self-refuting”.10

However, “brains made of atoms” and “computer-generated brains” need not be mutually exclusive. One might argue that we are brains in vats, and that the brains and vats in the computer-generated reality experienced by us are themselves made of atoms and molecules. There are then two kinds of atoms and molecules: those which we experience, or which make up the brains and vats we experience, and those which make up the computer that generates the reality we experience. But why then stop at two? For the computer generating the reality we experience could itself belong to a reality created by a computer, and this higher-order or meta computer could in turn belong to a reality created by another computer — and so on in matryoshka-like fashion.

Later Hilaries

A later avatar of Putnam’s accepts the brains-in-vats argument as it stands, which relies on the simultaneous use of mutually inconsistent languages, but does not accept the conclusion of the earlier Putnam, which was that it refutes externalism. At the time he presented the argument, he envisaged only two possible positions —his own internal realism and an external/metaphysical realism — “a dichotomy I blush at today”.11 Internal realism says:

the notion of a “thing in itself” makes no sense; and not because “we cannot know the things in themselves.” This was Kant’s reason, but Kant, although admitting that the notion of a thing in itself might be “empty,” still allowed it to possess a formal kind of sense. Internal realism says that we don’t know what we are talking about when we talk about “things in themselves.”12

Disavowing the notion of a “thing in itself” was Putnam’s first step towards reclaiming externalism.

To Kant, our knowledge is founded on sense data or sense impressions. Sense impressions are what is given to us. The external world is constructed using concepts that derive their meanings from the logical structure of human thought and the spatiotemporal structure of human sensory experience. But sense impressions are not all that is given to us. As Peter Strawson has demonstrated, what is “given with the given” is a realist descriptive scheme. And this entails not only that the things we perceive are external to us but also that they are causally responsible for being perceived by us. We cannot help thinking of the objects we perceive as external to us, nor can we help thinking of them as causally responsible for our perceiving them.

Taking Strawson’s hint, Putnam’s later avatar embraces “externalism about the mind” in the following sense: “To have concepts it is necessary to have appropriate causal connection with an environment.”

[I]f to have a mind is to have thoughts, then to have a mind ... you have to be hooked up to an environment in the proper way, or at least to have a mind that can think about an external world, you have to have causal interactions that extend into the environment.13

This externalism applies not only to thoughts and concepts but also to sense modalities like seeing:

[I]f to see a television set, in the sense in which a master of the relevant part of a language can see a television set, requires concept-possession, and concept-possession requires causal connection to external things, then seeing requires causal connection to external things.... [S]eeing, in the sense of perceiving by means of sight, requires a history of language acquisition and language use.14

This supports the brains-in-vats argument, inasmuch as it establishes that “the difference that makes a difference” between brains in vats and brains in bodies “lies at the ‘other end’ of the causal chains connecting us with” what we perceive.15 At the same time it externalizes the mind, extending it over and across the environment: “the mind isn’t a thing with a location at all (so it is not simply the brain under another name), but a system of world-involving abilities and exercises of those activities”.16 Getting rid of the thing-in-itself makes it possible to externalize the mind, and externalizing the mind makes it possible to internalize the world without internalizing it, i.e., without juxtaposing it with a world-in-itself.

“If one must use metaphorical language,” one of the Hilaries wrote,17 “then let the metaphor be this: the mind and the world jointly make up the mind and the world.” He thus rejected not only the view that the world “makes up the mind,” as externalism holds, but also the view that the mind “make up the world,” as internalism holds. A later Putnam goes further: “if I have long repented of having once said that ‘the mind and the world make up the mind and the world,’ that is because what we actually make up is not the world, but language games, concepts, uses, conceptual schemes”.18

As we learn more and as our needs and interests change, our conceptual schemes evolve. Therefore, we should embrace what some Putnam commentators19 have called “ontological pluralism”: there is no one “true” scheme; what there is depends in part on schemes or systems of concepts we find it convenient to deploy. Ontological pluralism, admirable in its epistemological humility, appears to be the final verdict of Putnam’s last avatar.

Added on May 27, 2023: For more on Ontological Pluralism see the next post.

In: E. von Glasersfeld, Radical Constructivism: A Way of Knowing and Learning, p. 26 (Routledge/Falmer, 1995).

H. Putnam, Reason, Truth and History, p. 64 (Cambridge University Press, 1981).

E. von Glasersfeld, An introduction to radical constructivism, in: P. Watzlawick (ed.), The Invented Reality, pp. 17–40.

The epithet “radical” was intended in the sense used by William James in his Essays in Radical Empiricism (Harvard University Press, 1912), i.e., “going to the roots” or “uncompromising.”

John Locke, too, made use of the metaphor of lock and key, but in a different sense. While, to von Glasersfeld, the same key can open many different locks and the same lock can be opened by many different keys, to Locke the relationship between lock and key is rather one-to-one.

P. Watzlawick (ed.), The Invented Reality, pp. 13–15 (Norton, 1984).

J.L. Austin, Sense and Sensibilia, pp. 11–12 (Oxford University Press, 1962).

D. Dennett and A. Steglich-Petersen (eds.), The Philosophical Lexicon (2008).

R.W. Emerson, Self-reliance, in: B. Atkinson (ed.), The Complete Essays and Other Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, p. 152 (The Modern Library, 1940).

H. Putnam, Reason, Truth and History, p. 7.

H. Putnam, Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity, p. 71 (Harvard University Press, 2016).

H. Putnam, The Many Faces of Realism, p. 36 (Open Court, 1987).

H. Putnam, Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity, p. 223.

Loc. cit. p. 225.

Loc. cit. p. 218.

Loc. cit. p. 181.

H. Putnam, Reason, Truth and History, p. xi.

R.E. Auxier, D.R. Anderson, and L. E. Hahn, The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam, p. 87 (The Library of Living Philosophers, 2015).

For instance: M. Baghramian, Reading Putnam (Routledge, 2013); J. Heil, Hilary Putnam, in A.P. Martinich and David Sosa (eds.), A Companion to Analytic Philosophy (Blackwell, 2001).