Messages and messengers from the beyond

Two early essays by Sri Aurobindo

In 1909, a few months before his departure from Calcutta (in February 1910) and his arrival in Pondicherry (in April 1910), Sri Aurobindo wrote the two pieces reproduced below. First published in the Karmayogin in November 1909 and January 1910, respectively, they are now included in Sri Aurobindo’s Essays in Philosophy and Yoga (pp. 38‒46). The Karmayogin was “A Weekly Review of National Religion, Literature, Science, Philosophy, etc.,” of which Sri Aurobindo was the editor. It appeared between June 1909 (the month after Sri Aurobindo’s acquittal and release from Alipore jail) and February 1910.

The dramatis personae

William Thomas Stead (5 July 1849 ‒ 15 April 1912). An English newspaper editor and pioneer of investigative journalism. His “new journalism” paved the way for the modern tabloid in Great Britain. Having frequently predicted that he would die either by lynching or by drowning, Stead did drown in the Titanic disaster on 15 April 1912, while travelling to speak on world peace at the Great Men and Religions conference in New York city on 22 April. He was last seen leading women and children to the safety of the stricken liner’s lifeboats. Testimonies from the Titanic’s survivors commented on the stoic and contemplative way that Stead faced his fate.

Lord (George Nathaniel) Curzon (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925). A prominent British statesman and writer, who served as Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905.

William Ewart Gladstone (29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898). A British statesman who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom for 12 years, spread over four non-consecutive terms beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894.

Benjamin Disraeli, a.k.a. Lord Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 ‒ 19 April 1881). A British statesman and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. (Mark Twain, to whom the statement “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics” is usually attributed, referred to the same in his autobiography as a “remark attributed to Disraeli.”)

John Nevil Maskelyne (22 December 1839 – 18 May 1917). An English stage magician and inventor. Many of his illusions are still performed today.

Prologue

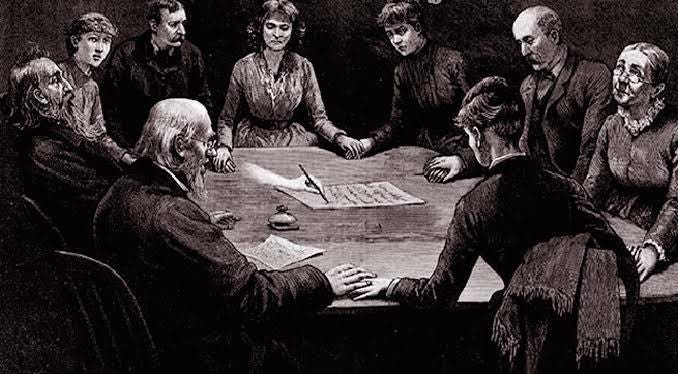

Spiritualism, which became popular in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century, centered on communicating with spirits of the dead via clairvoyant mediums, usually in the form of a séance. W.T. Stead entered his first séance (in 1881) ambivalent to the ghostly cause, yet he left energized by a “remarkable prophecy” from the spirit world: “Young man, you are going to be the St. Paul of Spiritualism”.1

In 1909 Stead founded Julia's Bureau, a public institution in London for communication with “the beyond.” In 1897, Stead published a collection of communications he received through automatic writing “from one who has gone before.” In the 1905 edition of the book, he states that the communications were received from “my friend Miss Julia who ‘what we call died’ on December 12, 1891” and that her friend “Ellen,” to whom the communications were addressed, “is still alive.” While it is easy to identify Stead’s deceased friend with the American journalist Julia A. Ames (October 14, 1861 ‒ December 12, 1891), the nature and extent of the identity of the source of the communications with the actual Ms. Ames remains open to question. In the aftermath of the first World War Julia’s Bureau became a source of support for the bereaved, reconnecting them with lost soldiers.

William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli, mentioned by Sri Aurobindo in the first piece below, were among the departed channeled by Stead. The chief historical connection between Stead and Gladstone was that Stead committed the Northern Echo, one of the most renowned British north country dailies of which he was the editor, not only to most of the agenda of the radical Liberals and the religious and social endeavors of the Salvation Army but also to the political leadership of Gladstone. Among his greatest successes with the paper was his contribution to Gladstone’s massive victory in the north country during the Midlothian election in 1880. As for Disraeli, Stead maintained an unrelenting opposition to his foreign and imperial policies.

What Sri Aurobindo had to say in 1909 on spiritualism was, first of all, that it is “impossible to dismiss the phenomena of spirit communications.” Obviously, “we have to be on our guard against a multitude of errors,” not least because the original communicant “has to give his thoughts at third hand.” His or her message passes first through the intermediary spirit (Julia or another) and then through the human medium before being conveyed to the sitters. This makes it virtually impossible to disengage the “the little of his own that the spirit can get in now and then” from (i) “the errors and self-deceptions of the medium and the sitters,” (ii) “the errors and self-deceptions of the communicant spirits, and, worst of all,” (iii) “deliberate deceit, lies and jugglery on the part of the visitants from the other world.”

The element of deceit and jugglery on the part of the medium and his helpers, while not always small, “can easily be got rid of.” But “error and self-deception from the other side of the veil cannot be obviated by any effort on this side.” All that can be safely affirmed is that, at least in some cases of automatic writing, “there was a communicant with superior powers to ordinary humanity using the hand of the writer. Who that was, Julia or another, ghost, spirit or other being, is a question that lies beyond.” Sri Aurobindo left it at that in 1909, and so do I for now.

Stead and the Spirits

Considerable attention has been attracted and excitement created by the latest development of Mr. W.T. Stead’s agency for communicant spirits which he calls Julia’s Bureau. The supposed communications of Mr. Gladstone, Lord Beaconsfield and other distinguished politicians on the question of the Budget have awakened much curiosity, ridicule and even indignation. The ubiquitous eloquence of Lord Curzon has been set flowing by what he considers this unscrupulous method of pressing the august departed into the ranks of Liberal electioneering agents, and he has penned an indignant letter to the papers in which there is much ornate Curzonian twaddle about sacred mysteries and the sanctities of the grave. If there is anything at all in the alleged communications from departed souls which have become of increasing interest to the European world, it ought to be fairly established that the grave is nothing but a hole in the earth containing a rotting piece of matter with which the spirit has no farther connection, and that the spirit is very much the same after death as before, takes much interest in small, trivial and mundane matters and is very far from regarding his new existence as a solemn, sacred and mysterious affair. If so, we do not see why we either should approach the departed spirit with long and serious faces or with any more unusual feelings than curiosity, interest and eagerness to acquire knowledge of the other world and communication with those we knew and loved in this, in fact, the ordinary human and earthly feelings existing between souls sundered by time and space, but still capable of communication. But Lord Curzon still seems to be labouring under the crude Christian conception of the blessed dead as angels harping in heaven whose spotless plumes ought not to be roughly disturbed by human breath and of spiritual communication as a sort of necromancy, the spirit of Mr. Gladstone being summoned from his earthy bed and getting into it again and tucking himself up comfortably in his coffin after Julia and Mr. Stead have done with him. We should have thought that in the bold and innovating mind of India’s only Viceroy these coarse European superstitions ought to have been destroyed long ago.

It is not, however, Lord Curzon but Mr. Stead and the spirits with whom we have to deal. We know Mr. Stead as a pushing and original journalist, not always over-refined or delicate either in his actions or expressions, skilful in the advertisement of his views, excitable, earnest, declamatory, loud and even hysterical, if you will, in some of his methods, but certainly neither a liar nor a swindler. He does and says what he believes and nothing else. It is impossible to dismiss his Bureau as an imposture or mere journalistic réclame. It is impossible to dismiss the phenomena of spirit communications, even with all the imposture that unscrupulous moneymakers have imported into them, as unreal or a deception. All that can reasonably be said is that their true nature has not yet been established beyond dispute.

There are two conceivable explanations, one that of actual spirit communication, the other that of vigorously dramatised imaginary conversations jointly composed with wonderful skill and consistency by the subconscious minds, whatever that may be, of the persons present, the medium being the chief dramaturge of this subconscious literary Committee. This theory is so wildly improbable and so obviously opposed to the nature of the phenomena themselves, that only an obstinate unwillingness to admit new facts and ideas can explain its survival, although it was natural and justifiable in the first stages of investigation. There remains the explanation of actual spirit communication. But even when we have decided on this hypothesis as the base of our investigation, we have to be on our guard against a multitude of errors; for the communications are vitiated first by the errors and self-deceptions of the medium and the sitters, then by the errors and self-deceptions of the communicant spirits, and, worst of all, by deliberate deceit, lies and jugglery on the part of the visitants from the other world. The element of deceit and jugglery on the part of the medium and his helpers is not always small, but can easily be got rid of. Cheap scepticism and cheaper ridicule in such matters is only useful for comforting small brains and weak imaginations with a sense of superiority to the larger minds who do not refuse to enquire into phenomena which are at least widespread and of a consistently regular character. The true attitude is to examine carefully the nature of the phenomena, the conditions that now detract from their value and the possibility of removing them and providing perfect experimental conditions which would enable us to arrive at a satisfactory scientific result. Until the value of the communications is scientifically established, any attempt to use them for utilitarian, theatrical or yet lighter purposes is to be deprecated, as such misuse may end in shutting a wide door to potential knowledge upon humanity.

From this point of view Mr. Stead’s bizarre experiments are to be deprecated. The one redeeming feature about them is that, as conducted, they seem to remove the first elementary difficulty in the way of investigation, the possibility of human deceit and imposture. We presume that he has got rid of professional mediums and allows only earnest-minded and honourable investigators to be present. But the other elements of error and confusion are encouraged rather than obviated by the spirit and methods of Mr. Stead’s Bureau. First, there is the error and self-deception of the sitters. The spirit does not express himself directly but has to give his thoughts at third hand; they come first to the intermediary spirit, Julia or another, by her they are conveyed to the human medium and through him conveyed by automatic or conscious speech or writing to the listeners. It is obvious how largely the mind of the medium and, to a smaller but still great extent, the thought-impressions of the other sitters must interfere, and this without the least intention on their part, rather in spite of a strong wish in the opposite direction.

Few men really understand how the human mind works or are fitted to watch the processes of their own conscious and half-conscious thought even when the mind is disinterested, still less when it is active and interested in the subject of communication. The sitters interfere, first, by putting in their own thoughts and expressions suggested by the beginnings of the communication, so that what began as a spirit conversation ends in a tangle of the medium’s or sitters’ ideas with the little of his own that the spirit can get in now and then. They interfere not only by suggesting what they themselves think or would say on the subject, but by suggesting what they think the spirit ought dramatically to think or say, so that Mr. Gladstone is made to talk in interminable cloudy and circumambient periods which were certainly his oratorical style but can hardly have been the staple of his conversation, and Lord Beaconsfield is obliged to be cynical and immoral in the tone of his observations. They interfere again by eagerness, which sometimes produces replies according to the sitters’ wishes and sometimes others which are unpleasant or alarming, but in neither case reliable. This is especially the case in answers to questions about the future, which ought never to be asked. It is true that many astonishing predictions occur which are perfectly accurate, but these are far outweighed by the mass of false and random prediction. These difficulties can only be avoided by rigidly excluding every question accompanied by or likely to raise eagerness or expectation and by cultivating entire mental passivity. The last however is impossible to the medium unless he is a practised Yogin, or in a trance, or a medium who has attained the habit of passivity by an unconscious development due to long practice. In the sitters we do not see how it is to be induced. Still, without unemotional indifference to the nature of the answer and mental passivity the conditions for so difficult and delicate a process of communication cannot be perfect.

Error and self-deception from the other side of the veil cannot be obviated by any effort on this side; all that we can do is to recognise that the spirits are limited in knowledge and cabined by character, so that we have to allow for the mental and moral equation in the communicant when judging the truth and value of the communication. Absolute deception and falsehood can only be avoided by declining to communicate with spirits of a lower order and being on guard against their masquerading under familiar or distinguished names. How far Mr. Stead and his circle have guarded against these latter errors we cannot say, but the spirit in which the sittings are conducted, does not encourage us to suppose that scrupulous care is taken in these respects. It is quite possible that some playful spirit has been enacting Mr. Gladstone to the too enthusiastic circle and has amused himself by elaborating those cloudy-luminous periods which he saw the sitters expected from the great deceased Opportunist. But we incline to the view that what we have got in this now famous spirit interview, is a small quantity of Gladstone, a great deal of Stead and a fair measure of the disembodied Julia and the assistant psychics.

Stead and Maskelyne

The vexed question of spirit communication has become a subject of permanent public controversy in England. So much that is of the utmost importance to our views of the world, religion, science, life, philosophy, is crucially interested in the decision of this question, that no fresh proof or disproof, establishment or refutation of the genuineness and significance of spirit communications can go disregarded. But no discussion of the question which proceeds merely on first principles can be of any value. It is a matter of evidence, of the value of the evidence and of the meaning of the evidence. If the ascertained facts are in favour of spiritualism, it is no argument against the facts that they contradict the received dogmas of science or excite the ridicule alike of the enlightened sceptic and of the matter-of-fact citizen. If they are against spiritualism, it does not help the latter that it supports religion or pleases the imagination and flatters the emotions of mankind. Facts are what we desire, not enthusiasm or ridicule; evidence is what we have to weigh, not unsupported arguments or questions of fitness or probability. The improbable may be true, the probable entirely false.

In judging the evidence, we must attach especial importance to the opinion of men who have dealt with the facts at first hand. Recently, two such men have put succinctly their arguments for and against the truth of spiritualism, Mr. W. T. Stead and the famous conjurer, Mr. Maskelyne. We will deal with Mr. Maskelyne first, who totally denies the value of the facts on which spiritualism is based. Mr. Maskelyne puts forward two absolutely inconsistent theories, first, that spiritualism is all fraud and humbug, the second, that it is all subconscious mentality. The first was the theory which has hitherto been held by the opponents of the new phenomena, the second the theory to which they are being driven by an accumulation of indisputable evidence.

Mr. Maskelyne, himself a professed master of jugglery and illusion, is naturally disposed to put down all mediums as irregular competitors in his own art; but the fact that a conjuror can produce an illusory phenomenon, is no proof that all phenomena are conjuring. He farther argues that no spiritualistic phenomena have been produced when he could persuade Mr. Stead to adopt conditions which precluded fraud. We must know Mr. Maskelyne’s conditions and have Mr. Stead’s corroboration of this statement before we can be sure of the value we must attach to this kind of refutation. In any case we have the indisputable fact that Mr. Stead himself has been the medium in some of the most important and best ascertained of the phenomena. Mr. Maskelyne knows that Mr. Stead is an honourable man incapable of a huge and impudent fabrication of this kind and he is therefore compelled to fall back on the wholly unproved theory of the subconscious mind.

His arguments do not strike us as very convincing. Because we often write without noticing what we are writing, mechanically, therefore, says this profound thinker, automatic writing must be the same kind of mental process. The one little objection to this sublimely felicitous argument is that automatic writing has no resemblance whatever to mechanical writing. [See the subsequent note on automatic.] When a man writes mechanically, he does not notice what he is writing; when he writes automatically, he notices it carefully and has his whole attention fixed on it. When he writes mechanically, his hand records something that it is in his mind to write; when he writes automatically, his hand transcribes something which it is not in his mind to write and which is often the reverse of what his mind would tell him to write. Mr. Maskelyne farther gives the instance of a lady writing a letter and unconsciously putting an old address which, when afterwards questioned, she could not remember. This amounts to no more than a fit of absent-mindedness in which an old forgotten fact rose to the surface of the mind and by the revival of old habit was reproduced on the paper, but again sank out of immediate consciousness as soon as the mind returned to the present. This is a mental phenomenon essentially of the same class as our continuing unintentionally to write the date of the last year even in this year’s letters. In one case it is the revival, in the other the persistence of an old habit. What has this to do with the phenomena of automatic writing which are of an entirely different class and not attended by absent-mindedness at all? Mr. Maskelyne makes no attempt to explain the writing of facts in their nature unknowable to the medium, or of repeated predictions of the future, which are common in automatic communications.

On the other side Mr. Stead’s arguments are hardly more convincing. He bases his belief, first, on the nature of the communications from his [deceased] son and others in which he could not be deceived by his own mind and, secondly, on the fact that not only statements of the past, but predictions of the future occur freely. The first argument is of no value unless we know the nature of the communication and the possibility or impossibility of the facts stated having been previously known to Mr. Stead. The second is also not conclusive in itself. There are some predictions which a keen mind can make by inference or guess, but, if we notice the hits and forget the misses, we shall believe them to be prophecies and not ordinary previsions.

The real value of Mr. Stead’s defence of the phenomena lies in the remarkable concrete instance he gives of a prediction from which this possibility is entirely excluded. The spirit of Julia, he states, predicted the death within the year of an acquaintance who, within the time stated, suffered from two illnesses, in one of which the doctors despaired of her recovery. On each occasion the predicting spirit was naturally asked whether the illness was not to end in the death predicted, and on each she gave an unexpected negative answer and finally predicted a death by other than natural means. As a matter of fact, the lady in question, before the year was out, leaped out of a window and was killed. This remarkable prophecy was obviously neither a successful inference nor a fortunate guess, nor even a surprising coincidence. It is a convincing and indisputable prophecy. Its appearance in the automatic writing can only be explained either by the assumption that Mr. Stead has a subliminal self, calling itself Julia, gifted with an absolute and exact power of prophecy denied to the man as we know him, — a violent, bizarre and unproved assumption, — or by the admission that there was a communicant with superior powers to ordinary humanity using the hand of the writer. Who that was, Julia or another, ghost, spirit or other being, is a question that lies beyond. This controversy, with the worthlessness of the arguments on either side and the supreme worth of the one concrete and precise fact given, is a signal proof of our contention that, in deciding this question, it is not a priori arguments, but facts used for their evidential value as an impartial lawyer would use them, that will eventually prevail.

Note on automatic writing (Record of Yoga, Note on the Texts, p. 1510)

Sri Aurobindo first tried automatic writing (defined by him as writing not “dictated or guided by the writer’s conscious mind”) towards the end of his stay in Baroda (that is, around 1904). He took it up “as an experiment as well as an amusement” after observing “some very extraordinary automatic writing” done by his brother Barin; “very much struck and interested” by the phenomenon, “he decided to find out by practising this kind of writing himself what there was behind it.” Barin seems at least sometimes to have used a planchette for his experiments, but Sri Aurobindo generally just “held the pen while a disembodied being wrote off what he wished, using my pen and hand”. He continued these experiments during his political career (1906–10) and afterwards. [In Part Five of his Record of Yoga] are published one example from 1907, an entire book received as automatic writing in 1910, and a number of examples from two years during which he also kept the Record: 1914 and 1920. His “final conclusion” about automatic writing

was that though there are sometimes phenomena which point to the intervention of beings of another plane, not always or often of a high order, the mass of such writings comes from a dramatising element in the subconscious mind; sometimes a brilliant vein in the subliminal is struck and then predictions of the future and statements of things known in the present and past come up, but otherwise these writings have not a great value.

The following letter is also germane to the subject at hand:

Automatic writings and spiritualistic séances are a very mixed affair. Part comes from the subconscious mind of the medium and part from that of the sitters. But it is not true that all can be accounted for by a dramatising imagination and memory. Sometimes there are things none present could know or remember; sometimes even, though that is rare, glimpses of the future. But usually these séances etc. put one into rapport with a very low world of vital beings and forces, themselves obscure, incoherent or tricky and it is dangerous to associate with them or to undergo any influence. Ouspensky and others must have gone through these experiments with too “mathematical” a mind, which was no doubt their safeguard but prevented them from coming to anything more than a surface intellectual view of their significance. [Letters on Yoga I, 568‒69]

Estelle W. Stead, “His First Séance,” in My Father: Personal and Spiritual Reminiscences, pp. 95‒103 (George H. Doran and Company, 1913).

Impossible to read this without thinking of Yeats, who I infinitely love (moved to Ireland just to be close to him). And I’m not going to mention PDO, who I deeply admired through a long period of my life (if not for what he was not, at least for what he was: another miglior fabbro of written language). Sri Aurobindo describes his major deficiency, which many of us unfortunately share, with his usual precision.

“For someone like Yeats, who emptied the contents of a solid education -which he never had- in search of the ecstasy that awaits mystical contemplation -which he never experienced, at least not in the sense that William James gives to that term- there was only one path open: support the pillars of that elusive world in superstition and experience the beyond through a similar theory. For the first he counted on automatic writing, and the invaluable help of his wife, Lady Hyde-Less, who got on wonderfully with the 'communicators'. The second was taken on by Yeats himself, joining the Theosophical Society in 1887. There he became adept to the occult, to Madame Blavatsky and to the Neoplatonists. Towards the end of his life he believed he saw an explanation of the Whole in the philosophy of Bishop Berkeley, more because of his Irish origin than thanks to any dogmatic idealism; although this fitted perfectly, or at least he saw it that way, with his belief in a spiritual world and in the artist as a contemplative being.

The result of all this: A Vision (1925). Where he tells us about the revolutions of the Sun and the Moon, the symbol of the cone, the twenty-eight (or was it twenty-nine?) incarnations and, as if that were not enough, he claims that this battered metaphysics has served him nothing less than to ‘enclose in a single thought reality and justice.’”

(AI, WBY o La Disciplina Del Estilo, Posdata, Insomnia N. 141, p.6, 2000)