Universal Consciousness and Compassion

A “Question of the Month” with Sri Aurobindo’s reply and story from the Kena Upanishad

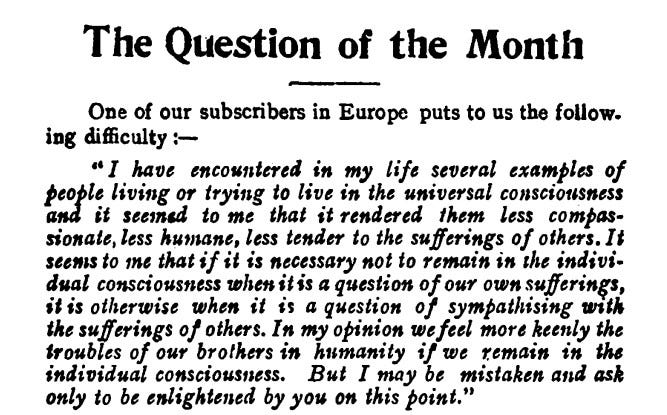

In the Arya of January 1915, one of the Review’s subscribers in Europe “puts to us the following difficulty”:

I have encountered in my life several examples of people living or trying to live in the universal consciousness and it seemed to me that it rendered them less compassionate, less humane, less tender to the sufferings of others. It seems to me that if it is necessary not to remain in the individual consciousness when it is a question of our own sufferings, it is otherwise when it is a question of sympathising with the sufferings of others. In my opinion we feel more keenly the troubles of our brothers in humanity if we remain in the individual consciousness. But I may be mistaken and ask only to be enlightened by you on this point.

The question posed by the subscriber seems to me to be of enduring relevance. Here is Sri Aurobindo’s reply1:

Is it certain that such people are living in the universal consciousness? or, if they are, is it certain that they are really less humane and compassionate? May they not be exercising their humanity in another fashion than the obvious and external signs of sympathy and tenderness?

If a man is really insensible to the experiences of others in the world, he is not living in the full universal consciousness. Either he has shut himself up in an experience of an individual peace and self-content, or he is absorbed by his contact with some universal principle in its abstract form without regard to its universal action, or he is living inwardly apart from the universe in touch with something transcendent of world-experience. All these states are useful to the soul in its progress, but they are not the universal consciousness.

When a man lives in the cosmic self, he necessarily embraces the life of the world and his attitude towards that world struggling upward from the egoistic state must be one of compassion, of love or of helpfulness. The Buddhists held that immersion in the infinite non-ego was in itself an immersion in a sea of infinite compassion. The liberated Sannyasin is described in the Gita and in other Hindu books as one whose occupation is beneficence to all creatures. But this vast spirit of beneficence does not necessarily exercise itself by the outward forms of emotional sympathy or active charity. We must not bind down all natures or all states of the divine consciousness in man to the one form of helpfulness which seems to us the most attractive, the most beautiful or the most beneficent. There is a higher sympathy than that of the easily touched emotions, a greater beneficence than that of an obvious utility to particular individuals in their particular sufferings.

The egoistic consciousness passes through many stages in its emotional expansion. At first it is bound within itself, callous therefore to the experiences of others. Afterwards it is sympathetic only with those who are identified in some measure with itself, indifferent to the indifferent, malignant to the hostile. When it overcomes this respect for persons, it is ready for the reception of the altruistic principle.

But even charity and altruism are often essentially egoistic in their immediate motive. They are stirred by the discomfort of the sight of suffering to the nervous system or by the pleasurableness of others’ appreciation of our kindliness or by the egoistic self-appreciation of our own benevolence or by the need of indulgence in sympathy. There are philanthropists who would be troubled if the poor were not always with us, for they would then have no field for their charity.

We begin to enter into the universal consciousness when, apart from all individual motive and necessity, by the mere fact of unity of our being with all others, their joy becomes our joy, their suffering our suffering. But we must not mistake this for the highest condition. After a time we are no longer overcome by any suffering, our own or others’, but are merely touched and respond in helpfulness. And there is yet another state in which the subjection to suffering is impossible to us because we live in the Beatitude, but this does not deter us from love and beneficence,—any more than it is necessary for a mother to weep or be overcome by the little childish griefs and troubles of her children in order to love, understand and soothe.

Nor is detailed sympathy and alleviation of particular sufferings the only help that can be given to men. To cut down branches of a man’s tree of suffering is good, but they grow again; to aid him to remove its roots is a still more divine helpfulness. The gift of joy, peace or perfection is a greater giving than the effusion of an individual benevolence and sympathy and it is the most royal outcome of unity with others in the universal consciousness.

“The gift of joy, peace or perfection is a greater giving than the effusion of an individual benevolence and sympathy and it is the most royal outcome of unity with others in the universal consciousness.”

The Kena Upanishad2 contains a charming story about the gods and the Eternal (Brahman, pronoun “It”), which makes much the same point. It goes like this:

The Eternal, using the gods as Its instruments, conquered, and “in the victory of the Eternal the gods grew to greatness.” But the gods thought: “Ours the victory, ours the greatness.”

Thereupon the Eternal appeared before them, “and they knew not what was this mighty Daemon.”

Then the gods said to Agni: “O thou that knowest all things born, learn of this thing, what may be this mighty Daemon.”

Agni rushed towards the Eternal and It said to him, “Who art thou?”

“I am Agni, I am he that knows all things born.”

“Since such thou art, what is the force in thee?”

“Even all this I could burn, all that is upon the earth.”

The Eternal then set before Agni a blade of grass and said: “This burn.” And Agni made towards it with all his speed but could not burn it.

Then the gods said to Vayu: “O Vayu, this discern, what is this mighty Daemon.”

Vayu rushed upon That, and It said to him: “Who art thou?”

“I am Vayu, and I am he that expands in the Mother of things.”

“Since such thou art, what is the force in thee?”

“Even all this I can take for myself, all this that is upon the earth.”

That set before him a blade of grass and said: “This take.” Vayu went towards it with all his speed but could not take it.

Then the gods turned to Indra: “Master of plenitudes, get thou the knowledge, what is this mighty Daemon.” But when Indra rushed upon It, It vanished from before him.

Eventually Indra chanced upon “the Woman, even Her who shines out in many forms, Uma daughter of the snowy summits.” To her he said: “What was this mighty Daemon?”

Uma replies: “It is the Eternal. Of the Eternal is this victory in which ye shall grow to greatness.”

And what is the nature of That, that mighty Daemon, this Eternal?

The name of That, the Upanishad concludes, is “That Delight”: “as That Delight one should follow after It. He who so knows That, towards him verily all existences yearn.”

Sri Aurobindo explains [p. 89]:

In [this] verse we have the culmination of the teaching of the Upanishad, the result of the great transcendence which it has been setting forth and afterwards the description of the immortality to which the souls of knowledge attain when they pass beyond the mortal status. It declares that Brahman is in its nature “That Delight”, Tadvanam. “Vana” is the Vedic word for delight or delightful, and “Tadvanam” means therefore the transcendent Delight, the all-blissful Ananda of which the Taittiriya Upanishad speaks as the highest Brahman from which all existences are born, by which all existences live and increase and into which all existences arrive in their passing out of death and birth. It is as this transcendent Delight that the Brahman must be worshipped and sought. It is this beatitude therefore which is meant by the immortality of the Upanishads. And what will be the result of knowing and possessing Brahman as the supreme Ananda? It is that towards the knower and possessor of the Brahman is directed the desire of all creatures. In other words, he becomes a centre of the divine Delight shedding it on all the world and attracting all to it as to a fountain of joy and love and self-fulfilment in the universe.

Sri Aurobindo, Essays in Philosophy and Yoga, pp. 453–55 (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 1998). URL: https://bit.ly/SriAurobindo-EPY.

Sri Aurobindo, Kena and Other Upanishads (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 2001). URL: https://bit.ly/SriAurobindo-Kena.

Yeah! Any other comment ?

I was somewhat surprised by the sentence: "And what will be the result of knowing and possessing Brahman as the supreme Ananda? It is that towards the knower and possessor of the Brahman is directed the desire of all creatures. In other words, he becomes a centre of the divine Delight shedding it on all the world and attracting all to it as to a fountain of joy and love and self-fulfilment in the universe."

In my humble view Brahman being infinite cannot be neither known nor possessed. Brahman is not an energy. What is named by the word "Brahman" in the text is a projection or a manifestation of the Divine Light that shines through the screen of the human mind acting as a mediator who transmutes the Divine Light (pure information) to communicate divine information by creating a materialised tool.