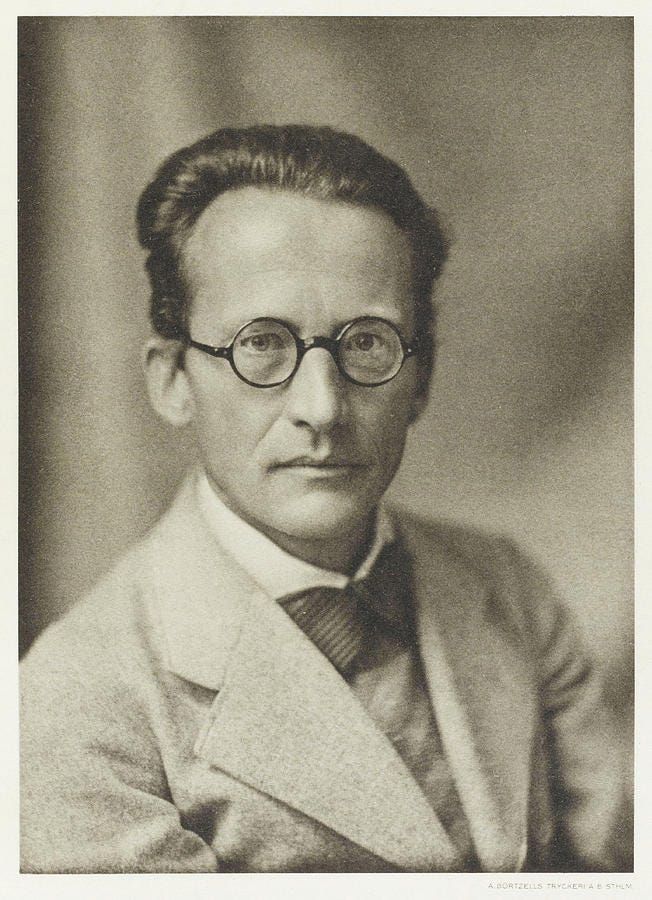

In a previous letter I mentioned Erwin Schrödinger’s astonishment at the fact that in spite of “the absolute hermetic separation of my sphere of consciousness” from everyone else’s, there is “a far-reaching structural similarity between certain parts of our experiences, the parts which we call external; it can be expressed in the brief statement that we all live in the same world.” To Schrödinger,1 this far-reaching structural similarity was “not rationally comprehensible. In order to grasp it we are reduced to two irrational, mystical hypotheses.” One of them was “the so-called hypothesis of the real external world.” We have seen what he thought of it. To postulate “a real world of bodies which are the causes of sense-impressions and produce roughly the same impression on everybody … means laying a completely useless burden on the understanding”—the burden of understanding the relation between the experienced world and an empirically inaccessible hypothetical world.

So what was the other irrational hypothesis—the one he endorsed? It was that

we are all really only various aspects of the One.

To Schrödinger, the multiplicity of minds “is only apparent, in truth there is only one mind. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads. And not only of the Upanishads.” The Upanishads are ancient Sanskrit texts, which contain many central concepts and ideas of classical Indian philosophy. If “to Western thought this doctrine has little appeal,” Schrödinger hastened to add,2 it was because

our science … is based on objectivation, whereby it has cut itself off from an adequate understanding of the Subject of Cognizance, of the mind. But I do believe that this is precisely the point where our present way of thinking does need to be amended, perhaps by a bit of blood-transfusion from Eastern thought. That will not be easy, we must beware of blunders—blood-transfusion always needs great precaution to prevent clotting. We do not wish to lose the logical precision that our scientific thought has reached, and that is unparalleled anywhere at any epoch.

“The One” mentioned by Schrödinger is the one Self of the Upanishads, the Ultimate Subject from which we are separated by a veil of self-oblivion. The same veil, according to the Upanishads, also prevents us from perceiving the Ultimate Object, as well as its fundamental identity with the Ultimate Subject. It prevents us from perceiving that the world is something that the One (qua Ultimate Object) manifests to itself (qua Ultimate Subject)—and therefore to us who are but “various aspects of the One.”

If at bottom we are all the same subject—without being aware of it, except by a genuinely mystical experience that is hard to come by—then we have to conceive of two poises of consciousness or modes of awareness, one in which the One manifests the world to itself aperspectivally, as if experienced from no particular location or from everywhere at once, and one in which the One manifests the world to itself perspectivally, as if experienced by a multitude of subjects from a multitude of locations.

In an aperspectival consciousness, the subject is where its objects are; it knows them by identity. To know an object is to be that object. In the view of the Upanishads, what ultimately exists is at once, indistinguishably, a consciousness that contains, a substance that constitutes, and an infinite quality and/or delight (ānanda) that experiences and expresses itself in form and movement.

If the One is essentially an infinite, self-existent and self-aware, quality and/or delight, one understands why the One would adopt a multitude of standpoints within the world that it manifests to itself: a mutual creative self-experience offers a greater variety of delight than a solitary one. As the One adopts a multitude of localized standpoints, the distantiating viewpoint of perspectival consciousness comes into being. Concurrently, experience acquires the familiar dimensions of phenomenal space—viewer-centered depth and lateral extent. Once the world is viewed in perspective, objects are seen from “outside,” as presenting their surfaces. At the same time, the dichotomy between subject and object becomes a reality, for a subject identified with an individual form cannot be overtly identical with the substance that constitutes all forms.

If the One adopts a multitude of localized standpoints, knowledge by identity takes the form of direct knowledge: each individual knows the others directly, without mediating representations. But if the One identifies itself with each particular form or standpoint to the exclusion of all others, as it does in our case, knowledge of other forms is reduced to an indirect knowledge, i.e., a direct knowledge by the individual of some of its own attributes (think electrochemical pulses in a brain), which serve as representations of other forms.

I suppose we can all appreciate the advantage of an ontology that has at its core an infinite Quality/Delight, over a framework of thought according to which what is ultimately real is a multitude of entities (elementary particles or spacetime points) lacking intrinsic quality or value. In many traditions such a multiplicity is fittingly referred to as “dust.” But why should a self-existent infinite quality and/or delight not only adopt a multitude of standpoints but also identify itself with each to the (apparent) exclusion of the others? The answer is to be found in the nature of the self-manifestation of the One in which we find ourselves as various aspects of the One. The main plot of this manifestation is a cycle of self-concealment and self-discovery.

From the point of view of the Upanishads, evolution presupposes involution. Involution is brought about by a stepwise departure from the original status of the One as at once an all-containing consciousness, an all-constituting substance, and an infinite quality, value, or delight. The first step towards involution is individuation. One nice thing about the process of individuation is that we can feel as if we understand it. We all know first-hand what it means to imagine things. So we can easily conceive of a consciousness that creates its own content. With a little effort we can also conceive of consciousness as simultaneously adopting a multitude of standpoints, and of some or all of its creative activity as simultaneously proceeding from these several standpoints. We also know first-hand the phenomenon of exclusive concentration, when awareness is focused on a single object or task, while other goings-on are registered, and other tasks attended to, subconsciously, if at all.

Involution begins in earnest when the multiple concentration of the One becomes exclusive, when (that is to say) the individual subjects lose sight of their mutual identity and, as a result, lose access to the aperspectival view of things. Carried further, involution renders consciousness implicit in its aspect of formative force. Carried further still, it renders the aspect of formative force implicit in forms it creates. And carried to its furthest extreme, it renders the principle of form implicit in a multitude of formless entities. And since formless entities are indistinguishable and therefore (by the Identity of Indiscernibles) numerically identical, involution ends with the One effectively deprived of its innate consciousness and self-determining force: the Ultimate Subject, infinitely creative, rendered implicit in the Ultimate Object. This (or something much like it) is how the stage for the adventure of evolution was set.

The Identity of Indiscernibles is a principle of ontology which states that no two distinct things exactly resemble each other. Hence if two things exactly resemble each other—as formless entities tend to do—they are numerically identical. Numerical identity is the relation that holds between two relata when they are the selfsame entity, or when the relations that hold are self-relations. In physics, numerical identity obtains between particles of the same type. In his Nobel lecture, Richard Feynman recalled:

I received a telephone call one day at the graduate college at Princeton from Professor Wheeler, in which he said, ‘Feynman, I know why all electrons have the same charge and the same mass.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Because, they are all the same electron!’

We have now strayed, inexorably, into the vexing territory of theodicy: what could justify this adventure, considering all the pain and suffering that (in hindsight) it entails? Certainly not an extra-cosmic Creator imposing these evils on his creatures. But the One of the Upanishads is no such monster; it imposes these things on itself. Sri Aurobindo3 does not mince words in describing this atrocious state of affairs:

For this is the monstrous thing, the terrible and pitiless miracle of the material universe that out of this no-Mind a mind or, at least, minds emerge and find themselves struggling feebly for light, helpless individually, only less helpless when in self-defence they associate their individual feeblenesses in the midst of the giant Ignorance which is the law of the universe. Out of this heartless Inconscience and within its rigorous jurisdiction hearts have been born and aspire and are tortured and bleed under the weight of the blind and insentient cruelty of this iron existence, a cruelty which lays its law upon them and becomes sentient in their sentience, brutal, ferocious, horrible. But what after all, behind appearances, is this seeming mystery? We can see that it is the Consciousness which had lost itself returning again to itself, emerging out of its giant self-forgetfulness, slowly, painfully, as a Life that is would-be sentient, half-sentient, dimly sentient, wholly sentient and finally struggles to be more than sentient, to be again divinely self-conscious, free, infinite, immortal. [LD 258]

But still—why? What can possibly justify such a cycle of self-concealment and self-discovery? Imagine for a moment that you are all-powerful and all-knowing (as in fact you are, essentially even though as yet only potentially). Could you experience the joy of winning a victory, of overcoming difficulties and oppositions, of making discoveries, of being surprised? You could not. To make all of this possible, you impose limitations on your inherent power and knowledge. Sri Aurobindo explains:

a play of self-concealing and self-finding is one of the most strenuous joys that conscious being can give to itself, a play of extreme attractiveness. There is no greater pleasure for man himself than a victory which is in its very principle a conquest over difficulties, a victory in knowledge, a victory in power, a victory in creation over the impossibilities of creation…. There is an attraction in ignorance itself because it provides us with the joy of discovery, the surprise of new and unforeseen creation…. If delight of existence be the secret of creation, this too is one delight of existence; it can be regarded as the reason or at least one reason of this apparently paradoxical and contrary Lila. [LD 426-27]

Līlā is a term of Indian philosophy which describes the manifested world as the field for a joyful sporting game made possible by self-imposed limitations.

How do the laws of physics fit into this scheme of things? If the force at work in the world is an infinite force working under self-imposed constraints, we can stop being spooked by the apparent inexplicability of the correlations that are predicted by quantum mechanics, the general theoretical framework of contemporary physics. (See here and here; more to come.) There is no need for mechanical or naturalistic explanations of the working of an infinite force. What we need to ask is why the force at work in the world works under constraints, and why the constraints have the particular form that they do.

As we just saw, the purpose for which that force has subjected itself to constraints was to set the stage for the drama of evolution. It stands to reason that these constraints must allow for the existence of sufficiently stable and re-identifiable objects. And because these have to be manifested by means of spatial relations (or relative positions) between formless relata, the spatial relations (as well as the corresponding relative momenta) must be indefinite, uncertainty relations must hold, the relata must be fermions—in short, something very much like quantum mechanics must hold (details can be found here and here).

A force working under self-imposed constraints is also capable of lifting its constraints. Their purpose was to set the stage for the drama of evolution, not to direct the drama. We are actors in this drama, and if our free will is limited, it is not because it is illusory. Needless to say, there is but one way in which freedom can be complete, and this is to become the sole determinant of all goings-on in the world. We are in possession of true freedom to the extent that we are not only consciously but also dynamically identified with the One. Absent this identification, our sense of being the owner of a libertarian free will is a misappropriation of a power which belongs to a deeper, subliminal self, and which often works towards goals that are at variance with our conscious intentions.

The philosopher John Searle4 once asked: “If you were designing an organic machine to pump blood you might come up with something like a heart, but if you were designing a machine to produce consciousness, who would think of a hundred billion neurons?” Even if brains do not produce consciousness— they are merely instrumental in its emergence from involution—we may want to know the reason for such enormous complexity. It boils down to this: the first aim of the force at work in the world—once the stage for the drama of evolution has been set—is to bring into play the principles of life and mind. Owing to the Houdiniesque nature of this manifestation, this has to be accomplished through tightly constrained modifications of the physical laws. As a consequence, the evolution of life necessitates the creation of increasingly complex organisms, and the evolution of mind necessitates the creation of increasingly complex nervous systems.

Evolution is far from finished. When life emerged, what essentially emerged was the power to execute creative ideas. When mind (or consciousness as we know it) emerged, what essentially emerged was the power to generate such ideas. The true nature of these principles is obscured by the fact that the requisite anatomy must first be established, and the more pressing tasks of self-preservation and self-replication must first be attended to. What has yet to emerge is the power to develop into expressive ideas the infinite Quality at the heart of reality. When this happens, the entire creative process—i.e., the development of Quality into Form using mind to generate expressive ideas and life to execute them—will be conscious and deliberate.

If all this sounds phantasmagoric, it is in large part because our theoretical dealings with the world are conditioned by the manner in which we, at this point in history, experience the world. We conceive of the evolution of consciousness, if not as a sudden lighting up of the bulb of sentience, then as a progressive emergence of ways of experiencing a world that exists independently of being experienced.

There is no such world. There are only different ways in which the One manifests the world to itself. These different ways have been painstakingly documented by Jean Gebser.5 One characteristic of the “structures of consciousness” that have successively emerged or are on the verge of emerging is their dimensionality. An increase in the dimensionality of the consciousness to which the world is manifested is tantamount to an increase in the dimensionality of the manifested world.

Consider, by way of example, the consciousness structure that immediately preceded the present and still dominant one. One of its characteristics is the notion that the world is enclosed in a sphere, with the fixed stars attached to its boundary, the firmament. We cannot but ask: what is beyond that sphere? Those who held this notion could not, because for them the third dimension of space—viewer-centered depth—did not at all have the reality it has for us. Lacking our sense of this dimension, the world experienced by them was in an important sense two-dimensional. This is why they could not handle perspective in drawing and painting, and why they were unable to arrive at the subject-free “view from nowhere,” which is a prerequisite of modern science. All this became possible with the consolidation, during the Renaissance, of our characteristically three-dimensional consciousness structure.

Our very concepts of space, time, and matter are bound up with our present consciousness structure. This made it possible to integrate the location-bound outlook of a characteristically two-dimensional consciousness into an effectively subject-free world of three-dimensional objects. Matter as we know it was the result. It is not matter that has created consciousness; it is consciousness that has created matter, first by its self-concealment, or involution, in an apparent multitude of formless particles, and again by evolving our present mode of experiencing the world. Ahead lies the evolution of a consciousness structure—and thereby of a world—that transcends our time- and space-bound perspectives. Just as the mythological thinking of the previous consciousness structure could not foresee the technological explosion made possible by science, so science-based thinking cannot foresee the consequences of the birth of a new world, brought about, not by technological means, but by a further increase in the dimensionality of consciousness.

E. Schrödinger. What is real? In My View of the World (Cambridge University Press, 1964).

E. Schrödinger. The Arithmetical Paradox: The Oneness of Mind. In What Is Life? With: Mind and Matter & Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Sri Aurobindo. [LD=] The Life Divine (Sri Aurobindo Publication Department, 2005). https://bit.ly/SriAurobindo-TLD.

J.R. Searle (1995). The Mystery of Consciousness. The New York Review of Books. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1995/11/02/the-mystery-of-consciousness/

J. Gebser. The Ever-Present Origin (Ohio University Press, 1986).

The “aperspectivally” point is essentially that of “il fondamento senza fondo”, or the form of the formless so prevalent in mahāyānic buddhism. The “perspectivally” manifestaron is obviously that of Leibniz’ monadic order. We in the West are the children of Aristotelean logic, there is no escape from it, and in that sense we have never gone beyond a simple logic of the subject (that which cannot be predicated of any object). What Schrödinger was so keen to preserve, justifiably, starts there, passes through Kant and ends up in its ultimate cognitive exposure (non multa sed multum) with Nishida.