Claire Berlinski (and Geoffrey Marcy) on Greenland + Robert Kagan (and Berlinski) on Russia and Ukraine

Footnotes to my last post (The Descent into Night)

Claire Berlinski has a long and important post out at The Cosmopolitan Globalist. The first part is about Trump’s recent press conference. This I will spare you, but if you are ready for a massive helping of insanity, you can read Berlinski’s excerpts and comments here. (This is also the link to her post in its entirety.)

1. Greenland

In the second part of her post, Berlinski quotes an email she received from astronomer Geoff Marcy regarding Trump’s obsession with Greenland. (If this doesn’t interest you, please skip to the part on Russia and Ukraine below.)

Journalists, wondering how on earth it occurred to Trump that the United States must possess Greenland, have speculated that it’s because Greenland looks big on a Mercator map. This doesn’t seem to be the case. Here is the email:

Greenland plays a critical role in the defense of the United States against Russian ballistic missiles due to its strategic location in the Arctic, directly along potential flight paths of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) launched from Russia towards North America.

Greenland hosts the Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base), a major US military installation. It is a key component of the US missile defense system, which operates advanced radar systems capable of detecting and tracking incoming missiles early in their trajectory. This early warning capability provides essential time for response measures, including intercepts by US ground- or sea-based missile defense systems.

Greenland’s location supports broader Arctic surveillance, including of shipping lanes, and enhances US and NATO strategic presence in a region increasingly contested by Russian military activities. By maintaining robust operations in Greenland, the US strengthens its northern defenses and reinforces deterrence against potential missile threats.

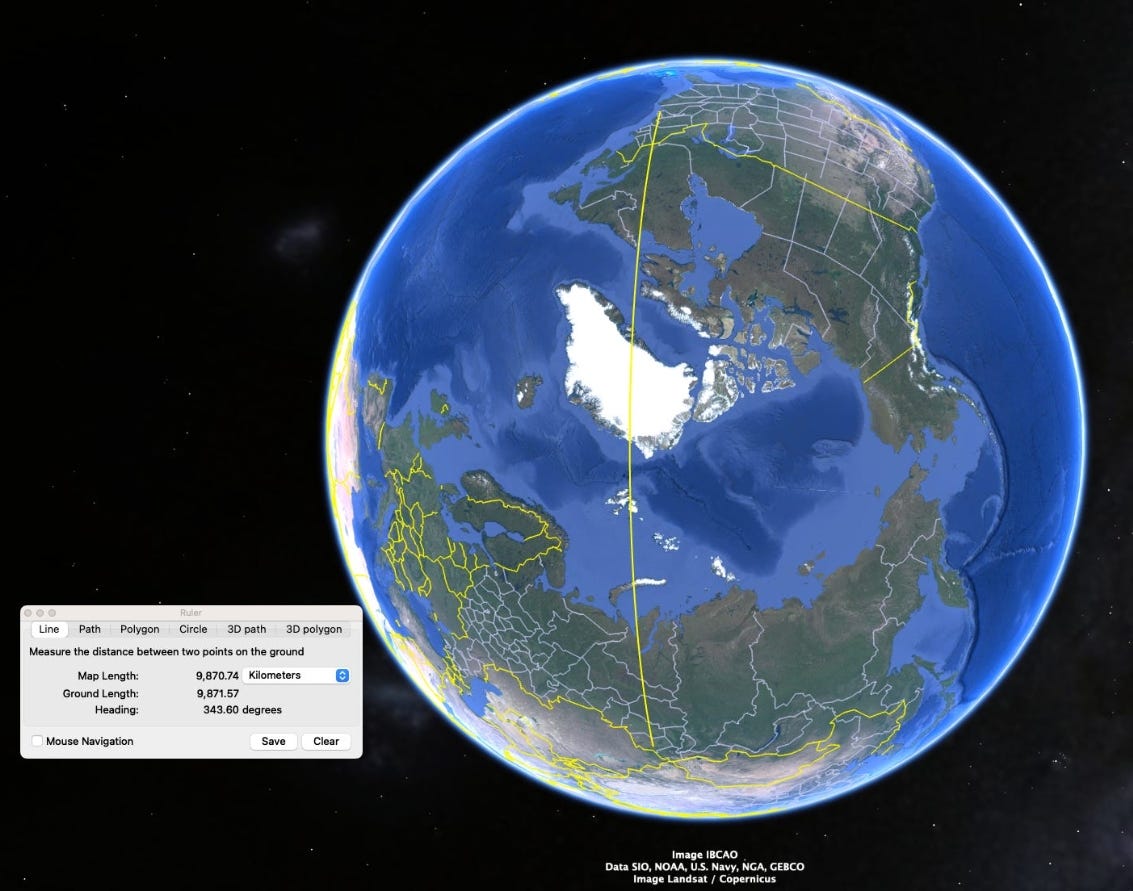

The missile silos housing Russia’s 1,700 ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads are scattered throughout western and southern Russia. The ballistic path above the atmosphere from the Russian missile silos toward the East Coast of the United States passes directly over Greenland. A ballistic path is simply a sub-orbital trajectory, like the arc of a fast baseball under gravity, which is a part of a “great circle.”

The ballistic path from one Russian missile silo to Washington DC is shown in the graphic here:

Russia’s ballistic missile silos are primarily located in strategic regions across the country, designed to enhance survivability and operational readiness. The silos house intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and are managed by Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces (RVSN).

At this point Marcy lists six key locations, specifying the ICBMs they house. (For the details see Berlinski’s post.)

The geographic distribution of Russian silos also ensures coverage of the United States and other strategic targets while providing redundancy and resilience against a first-strike scenario. The locations are often remote, enhancing survivability against preemptive attacks.

Marcy then turns to the US Pituffik Space Base in Greenland (formerly known as Thule Air Base):

Pituffik is the northernmost US military base, positioned at a pivotal point for monitoring ballistic missile activity and conducting space surveillance. Its location makes it an essential part of early warning systems, particularly against missile launches from potential adversaries like Russia.

The base hosts a Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) radar, which provides critical data on intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launches. This radar is part of the broader US and NATO defense network, enhancing North American and European security.

Pituffik contributes to the Space Surveillance Network (SSN) by tracking satellites and space debris, ensuring safe operations in Earth’s orbit. It also supports space-based assets critical to military communications and global navigation.

As Arctic activity increases due to climate change and geopolitical competition, Pituffik is vital for maintaining US presence and readiness in the region. It provides logistical and operational support for US and allied missions in the Arctic.

Established in 1951, the base has long served as a cornerstone of US Arctic strategy. Its location in Greenland underscores the importance of US-Danish cooperation, as Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark.

The base was renamed in 2023 to reflect its role within the US Space Force and its importance in space-related defense and surveillance missions. The name "Pituffik" comes from the local Greenlandic language, honoring the area’s heritage.

In summary, Pituffik Space Base in Greenland is a linchpin in US strategic defense and space operations, leveraging its Arctic location for early warning, space surveillance, and strengthening the US presence in a geopolitically vital region.

To this, Berlinski adds “just a few more points”:

As ice melts due to climate change, new shipping routes such as the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage are opening. Greenland will probably become a major hub for maritime traffic and trade.

Much more importantly, significant geological surveys indicate that Greenland is the most promising location for rare earth element mining outside of China. The Kvanefjeld plateau, in southern Greenland is known to contain one of the world's largest deposits of neodymium, praseodymium, lanthanum, and cerium, which are essential for manufacturing magnets, batteries, and other high-tech components.

Another major site, the nearby Tanbreez deposit, contains high concentrations of zirconium, niobium, and tantalum. These are vital for aerospace technologies, electronics, and superconductors. The broader Ilimaussaq intrusive complex, which includes the Kvanefjeld area, is rich in rare minerals such as eudialyte and steenstrupine.

Among the rare earths known to exist in Greenland in ample supply are neodymium (used in powerful permanent magnets for wind turbines, electric vehicles, and electronics); praseodymium (high-strength magnets and alloys) lanthanum (optics, batteries, and catalysts), cerium (catalytic converters, glass polishing, and LEDs), dysprosium and terbium (high-temperature magnets used in electric vehicles), and zirconium and niobium (structural materials in aerospace and advanced electronics).

Advanced military technology, in particular, requires dysprosium and terbium. Dysprosium and terbium are added to NdFeB magnets to enhance their performance at high temperatures. These enhanced magnets are essential to the gyroscopes, accelerometers, and control systems on precision-guided missiles, not to mention the advanced sonar systems used in submarines. Terbium-doped materials are used in laser systems to increase their efficiency and performance in missile defense and drone interception. Want a secure, high-frequency communication system? You need dysprosium and terbium. Want jamming device devices and electronic countermeasures? You need dysprosium and terbium. Want high-performance motors in your UAVs? Military robots?

You get the idea. I imagine they’re rather important to rocketry, as well. And did I mention electric vehicles?

Right now, China accounts for 80 to 90 percent of global rare earth production and an even larger share of the processing capacity. Our military, for obvious reasons, regards this situation with concern.

Greenland was colonized by Denmark in the early 18th century, though it had been inhabited by Inuits for thousands of years. Danish rule brought the usual indignities of European colonization. In 1953, Greenland formally became part of Denmark; whereas before it was a colony, afterward it was “an autonomous region.” The change gave Greenlanders Danish citizenship. It also formalized Danish control over Greenland’s affairs.

In 1979, Greenland’s independence movement achieved a significant victory when Greenland was granted home rule, allowing for the creation of its own parliament and government. This system devolved powers to Greenland in arenas like education, health, and—most importantly for our purposes—authority over its natural resources, meaning it is now up to Greenlanders to decide which mining activities to pursue. Denmark, meanwhile, oversees the territory’s foreign policy and defense.

As you might expect, the Greenland independence movement has been animated by a sense of grievance over colonialism and external governance. Many view their autonomy as a stepping stone to full independence, but the territory remains uncomfortably dependent on Denmark: Danish subsidies currently amount to a quarter of Greenland’s GDP.

Now the plot gets thick as sludge. The Kvanefjeld deposit also contains uranium. This has been a source of controversy. Obviously, uranium mining poses significant risks to the environment and human health. Dust, tailings, and waste byproducts contaminate the air, soil, and water—and they do so for a good long time. Greenland’s Arctic environment is particularly fragile. The potential for radioactive waste to enter water systems, especially given the melting ice sheet, is real. The indigenous Inuits largely support themselves by fishing and hunting. They are uneasy at the thought of irradiating their environment.

Denmark has historically discouraged uranium mining, fearing its impact on Greenland’s environment and Denmark’s reputation as a responsible actor in nuclear nonproliferation. Supporters of mining, however, note that exploiting these resources would diversify Greenland’s economy, create jobs, and generate revenue that would reduce Greenland’s dependence on Danish subsidies. This is important to a people who aspire to full independence.

In 2021, the left-wing Inuit Ataqatigiit party won Greenland’s parliamentary election on a platform staunchly opposed to uranium mining. Shortly after taking office, they made good on their promises, passing a law that banned uranium mining and effectively ending the development of the Kvanefjeld mine. But Chinese companies, such as Shenghe Resources, had invested in Greenland’s mining projects, particularly the Kvanefjeld site. The new law amounted to a considerable setback to China’s Arctic ambitions. It is not clear what China plans to do about it, but there are only about 56,000 Greenlanders.

As the fourth season of Borgen hints, Greenland’s Arctic waters, though largely unexplored, are thought to contain vast reserves of oil and natural gas.1

Are we sure it’s just because Trump can’t read a Mercator map? Maybe he can’t, but I suspect Musk can.

2. Russia and Ukraine

In the third part of her post, Berlinski summarizes (and quotes from) an article by Robert Kagan in The Atlantic. It’s titled, “Trump is facing a catastrophic defeat in Ukraine,” and the subtitle reads, “If Ukraine falls, it will be hard to spin it as anything but a debacle for the United States, and for its president.” The following text is hers, the quoted passages are from Kagan’s article.

Kagan argues—correctly—that without substantial new US aid, Ukraine will lose the war against Russia within 12 to 18 months, leading to a complete loss of sovereignty and full Russian control:

Ukraine will not lose in a nice, negotiated way, with vital territories sacrificed but an independent Ukraine kept alive, sovereign, and protected by Western security guarantees. …

This poses an immediate problem for Donald Trump. He promised to settle the war quickly upon taking office, but now faces the hard reality that Vladimir Putin has no interest in a negotiated settlement that leaves Ukraine intact as a sovereign nation. Putin also sees an opportunity to strike a damaging blow at American global power. Trump must now choose between accepting a humiliating strategic defeat on the global stage and immediately redoubling American support for Ukraine while there’s still time. The choice he makes in the next few weeks will determine not only the fate of Ukraine but also the success of his presidency.

Kagan rightly notes that the fall of Ukraine would be a humanitarian and strategic catastrophe. But Trump has promised to end the war quickly. Putin, Kagan writes, is resolute and unyielding. He has no intention of negotiating a settlement that allows Ukraine to maintain its independence. Any deal Trump might broker would, therefore, come at the cost of Ukrainian sovereignty—a compromise that would amount to a catastrophic defeat for American global leadership and the credibility of it all alliances.

Trump is promoting the notion—an outright nonsense—that the war was a response, indeed a natural response, to a NATO expansion that did not happen and was not in the cards. But as Kagan writes, again correctly,

The end of an independent Ukraine is and always has been Putin’s goal. While foreign-policy commentators spin theories about what kind of deal Putin might accept, how much territory he might demand, and what kind of security guarantees, demilitarized zones, and foreign assistance he might permit, Putin himself has never shown interest in anything short of Ukraine’s complete capitulation. … Western experts filling the op-ed pages and journals with ideas for securing a post-settlement Ukraine have been negotiating with themselves.

(Well said.) As Kagan moreover points out,

It is not at all clear that Putin even seeks the return to normalcy that peace in Ukraine would bring. In December, he increased defense spending to a record US$126 billion, 32.5 percent of all government spending, to meet the needs of the Ukraine war. Next year, defense spending is projected to reach 40 percent of the Russian budget. (By comparison, the world’s strongest military power, the US, spends 16 percent of its total budget on defense.) Putin has revamped the Russian education system to instill military values from grade school to university. He has appointed military veterans to high-profile positions in government as part of an effort to forge a new Russian elite, made up, as Putin says, exclusively of “those who serve Russia, hard workers and [the] military.” He has resurrected Stalin as a hero. Today, Russia looks outwardly like the Russia of the Great Patriotic War, with exuberant nationalism stimulated and the smallest dissent brutally repressed.

Is all of this just a temporary response to the war, or is it also the direction Putin wants to steer Russian society? He talks about preparing Russia for the global struggles ahead. Continuing conflict justifies continuing sacrifice and continuing repression. Turning such transformations of society on and off and on again like a light switch—as would be necessary if Putin agreed to a truce and then, a couple of years later, resumed his attack—is not so easy. …

Russia faces problems, even serious problems, but Putin believes that without substantial new aid Ukraine’s problems are going to bring it down sooner than Russia.

That is the key point: Putin sees the timelines working in his favor. Russian forces may begin to run low on military equipment in the fall of 2025, but by that time Ukraine may already be close to collapse. Ukraine can’t sustain the war another year without a new aid package from the United States.

Thus when Putin contemplates the world, he sees a constellation of obliging stars aligning in his favor:

Putin will soon have an American president and a foreign-policy team who have consistently opposed further aid to Ukraine. The transatlantic alliance, once so unified, is in disarray, with America’s European allies in a panic that Trump will pull out of NATO or weaken their economies with tariffs, or both. Europe itself is at a low point; political turmoil in Germany and France has left a leadership vacuum that will not be filled for months, at best. If Trump cuts off or reduces aid to Ukraine, as he has recently suggested he would, then not only will Ukraine collapse but the divisions between the US and its allies, and among the Europeans themselves, will deepen and multiply. Putin is closer to his aim of splintering the West than at any other time in the quarter century since he took power.

Is this a moment at which to expect Putin to negotiate a peace deal?

Morally, the most important section of this article stresses what would happen to Ukraine should Russia win:

A Russian victory means the end of Ukraine. Putin’s aim is not an independent albeit smaller Ukraine, a neutral Ukraine, or even an autonomous Ukraine within a Russian sphere of influence. His goal is no Ukraine. “Modern Ukraine,” he has said, “is entirely the product of the Soviet era.” Putin does not just want to sever Ukraine’s relationships with the West. He aims to stamp out the very idea of Ukraine, to erase it as a political and cultural entity. …

The vigorous Russification that Putin’s forces have been imposing in Crimea and the Donbas and other conquered Ukrainian territories is evidence of the deadly seriousness of his intent. International human-rights organizations and journalists, writing in The New York Times, have documented the creation in occupied Ukraine of “a highly institutionalized, bureaucratic and frequently brutal system of repression run by Moscow” comprising “a gulag of more than 100 prisons, detention facilities, informal camps and basements” across an area roughly the size of Ohio. According to a June 2023 report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, nearly all Ukrainians released from this gulag reported being subjected to systematic torture and abuse by Russian authorities. Tortures ranged from “punching and cutting detainees, putting sharp objects under fingernails, hitting with batons and rifle butts, strangling, waterboarding, electrocution, stress positions for long periods, exposure to cold temperatures or to a hot box, deprivation of water and food, and mock executions or threats.” Much of the abuse has been sexual, with women and men raped or threatened with rape. Hundreds of summary executions have been documented, and more are likely—many of the civilians detained by Russia have yet to be seen again. Escapees from Russian-occupied Ukraine speak of a “prison society” in which anyone with pro-Ukrainian views risks being sent “to the basement,” where torture and possible death await.

… “The majority of victims,” according to the State Department, have been “active or former local public officials, human rights defenders, civil society activists, journalists, and media workers.” According to the OHCHR, “Russia’s military and their proxies often detained civilians over suspicions regarding their political views, particularly related to pro-Ukrainian sentiments.” … In schools throughout the Russian-occupied territories, students learn a Russian curriculum and complete a Russian “patriotic education program” and early military training, all taught by teachers sent from the Russian Federation. Parents who object to this Russification risk having their children taken away and sent to boarding schools in Russia or occupied Crimea, where, Putin has decreed, they can be adopted by Russian citizens. By the end of 2023, Ukrainian officials had verified the names of 19,000 children relocated to schools and camps in Russia or to Russian-occupied territory.

… These horrors await the rest of Ukraine if Putin wins. Imagine what that will look like. More than 1 million Ukrainians have taken up arms against Russia since February 2022. What happens to them if, when the fighting stops, Russia has gained control of the entire country? What happens to the politicians, journalists, NGO workers, and human-rights activists who helped in innumerable ways to fight the Russian invaders? … Some commentators argue that it would be better to let Ukraine lose quickly because that, at least, would end the suffering. Yet for many millions of Ukrainians, defeat would be just the beginning of their suffering.

The commentators who argue that it would be a favor to Ukraine to allow them to lose have no sense of history. Putin admires and models himself on the great monsters of Russian history. For Ukraine, losing the war will mean genocide and slavery. Is a pity that these words have become so debased that no one understands them anymore. Trump, writes Kagan,

now finds himself in a trap only partly of his own devising. … now [he] is in the position of having promised a peace deal that he cannot possibly get without forcing Putin to recalculate. …

Trump has a credibility problem, partly due to the Biden administration’s failures, but partly of his own making. Putin knows what we all know: that Trump wants out of Ukraine. He does not want to own the war, does not want to spend his first term in a confrontation with Russia, does not want the close cooperation with NATO and other allies that continuing support for Ukraine will require, and, above all, does not want to spend the first months of his new term pushing a Ukraine aid package through Congress after running against that aid. Putin also knows that even if Trump eventually changes his mind, perhaps out of frustration with Putin’s stalling, it will be too late. Months would pass before an aid bill made it through both houses and weaponry began arriving on the battlefield. Putin watched that process grind on last year, and he used the time well. He can afford to wait. After all, if eight months from now Putin feels the tide about to turn against him in the war, he can make the same deal then that Trump would like him to make now. In the meantime, he can continue pummeling the demoralized Ukrainians, taking down what remains of their energy grid, and shrinking the territory under Kyiv’s control.

The only way to escape this is to do exactly what Trump has promised not to do: He must persuade Putin that the United States will not allow Ukraine to fall. The only way to persuade him is by providing a significant amount of fresh aid—fast. Only this would change the timeline and thus Putin’s calculations. Putin, Kagan writes, must be made to understand the time isn’t on his side: His army will collapse before Ukraine is conquered.

Kagan stresses, and he’s right to do so, that Putin’s supreme objective is the defeat of the United States:

His goal for more than two decades has been to weaken the US and break its global hegemony and its leadership of the “liberal world order” so that Russia may resume what he sees as its rightful place as a European great power and an empire with global influence. Putin has many immediate reasons to want to subjugate Ukraine, but he also believes that victory will begin the unraveling of eight decades of American global primacy and the oppressive, American-led liberal world order. Think of what he can accomplish by proving through the conquest of Ukraine that even America’s No. 1 tough guy, the man who would “make America great again,” who garnered the support of the majority of American male voters, is helpless to stop him and to prevent a significant blow to American power and influence. In other words, think of what it will mean for Donald Trump’s America to lose. Far from wanting to help Trump, Putin benefits by humiliating him. It wouldn’t be personal. It would be strictly business …

Trump therefore faces what Kagan calls a paradox. He and the entourage around him share Putin’s hostility to the global order that the United States brought into being. They share Putin’s hostility to NATO. As Kagan points out, the original America First movement sought to prevent the United States from becoming a global power.2 But Trump’s problem is that “unlike his fellow travelers in anti-liberalism,” he will soon be the president of the United States.

The liberal world order is inseparable from American power, and not just because it depends on American power. … Trump can’t stop defending the liberal world order without ceding significantly greater influence to Russia and China. Like Putin, Xi Jinping, Kim Jong Un, and Ali Khamenei see the weakening of America as essential to their own ambitions. Trump may share their hostility to the liberal order, but does he also share their desire to weaken America and, by extension, himself? …

Today, not only Putin but Xi, Kim, Khamenei, and others whom the American people generally regard as adversaries believe that a Russian victory in Ukraine will do grave damage to American strength everywhere. That is why they are pouring money, weaponry, and, in the case of North Korea, even their own soldiers into the battle. Whatever short-term benefits they may be deriving from assisting Russia, the big payoff they seek is a deadly blow to the American power and influence that has constrained them for decades.

What’s more, America’s allies around the world agree. They, too, believe that a Russian victory in Ukraine, in addition to threatening the immediate security of European states, will undo the American-led security system they depend on. That is why even Asian allies far from the scene of the war have been making their own contributions to the fight.

I agree with every word he writes. But here, I begin to worry that his argument devolves into wishful thinking. Although he doesn’t say so explicitly, Kagan seems to think, or hope, that Trump’s terror of being a loser might militate against his worst instincts. Images of the fall of Afghanistan, Kagan reminds readers, permanently soured Americans on the Biden presidency, but those images would be as nothing compared to what we will see and hear when Ukraine falls.

He seems to be addressing his argument to Trump himself: “If you allow this to happen,” he is warning him, “you will be deeply unpopular. Americans will see you as weak. They will see you as a loser.”

But what if Trump has thought of this already?

And what if he has a plan for this?

Thus ends Berlinski’s summary of Bob Kagan’s article. In the final part of her post, Berlinski returns to the press conference, pointing out “that in his remarks about Ukraine, Trump is yet again serving as Putin’s ventriloquist.” This she substantiates in a lengthy footnote. In contrast to people arguing that Trump is just being Trump, parroting talking points from news sources echoing Kremlin propaganda and from the likes of Tucker Carlson, Elon Musk, and Tulsi Gabbard, Berlinski fears that

Trump does understand what he’s saying. But whereas Kagan hopes Trump will be loath to superintend over a strategic and moral catastrophe that would make him a loser forever in the eyes of a profoundly diminished America, Trump has already priced that in and figured out how he’ll avoid that. He reckons that acquiring Panama and Greenland—and for God’s sake, Canada—will distract Americans from their loss.

In this interpretation, Trump shares Putin’s vision of a world carved up into imperial zones of interest, with the United States becoming Greater America—through purchase or conquest, or perhaps nuclear blackmail—to compensate for the loss of its global power. He has either agreed to this with Putin explicitly, or he is counting on Putin to understand the implicit quid pro quo. His base, he reckons, will be so thrilled to be Greenland’s new imperial overlords that they’ll forget all about the destruction of Ukraine. And after he conquers Canada, too, a colossal sculpture of Donald Trump will be carved into the face of every mountain top in Greater America. He will be immortal. ...

I just can’t quite bring myself to believe it. It’s too fantastical, too horrible, too bizarre, too monstrous, too insane. (It also relies on the idea that Trump is vastly more intelligent and mentally organized than he appears, which I also can’t quite bring myself to believe.) The whole thing sounds like a novel—and it certainly sounds like a conspiracy theory. It can’t be real.

But can you explain why Trump’s vision coincides so perfectly with Vladimir Putin’s? Something beyond “it’s just coincidence?” If you can, please tell me, because this is terrifying me. I now very much fear that we’ll see the worst imaginable scenario in Ukraine, followed by the worst imaginable scenario in Europe and Asia.

When I allow myself to think that this might be reality—that the world will soon see horrors every bit the equal of 20th century’s, and worse—I find myself almost unable to breathe. I can only consider it, in all of its awfulness, for minutes at a time.

My God, I hope he’s just insane. Please let him just be insane.

Berlinski’s footnote: I’m given to understand that you can learn all about the subtleties of this by watching the Danish television show Borgen, recommended to me by my brother. Borgen is about the career of Birgitte Nyborg, a fictional Prime Minister of Denmark. In the fourth season, apparently, the tensions between the central government and the Greenlanders plays a central role in the storyline. (I haven’t watched it yet, but I do trust my brother.)

Berlinski’s footnote: If you've not read Lindberg’s infamous speech, “Who Are The War Agitators?” I cannot more strongly urge you to read it. It’s impossible to avoid the conclusion that all of these instincts are very deep aspects of our national character. They were somehow suppressed, through a cultural mechanism I simply don’t understand, for the entirety of the period between Pearl Harbor and Trump’s ride down the escalator.

There is something so odd about this, though. Fewer than one in a thousand Americans, I’d wager, have read that speech. Why did the America First movement—a name associated with the most discredited ideas in American history outside of chattel slavery—suddenly roar back to prominence in our national life, like a cancer after a remission? (Is it credible to think, as Trump claims, that he didn’t know the origin of the phrase? I genuinely don’t know.) Where did those ideas go, exactly, during the very long time when it would have occurred to no American to think or say these things?

It does make you wonder what other hideous thing, thought long-buried, is now gathering its strength and poised to return.

Well, I sincerely hope I'm wrong. It isn't that Trump has some brilliant (or insane) plan.

He doesn't need to.

It was never clearer (at least to me) than during the last months of the campaign. Honestly, for the majority of Trump supporters, what happens in the world of reality simply doesn't matter.

Trump could actually say (I know this is hard for people outside the US to believe), "I just negotiated the greatest peace deal in history. Ukraine is now independent and free."

And there could be daily news footage of Russia building hundreds, even thousands of detention centers, Ukrainian journalists, artists, politicians describing in precise terms the ghastly consequents of the complete Russian takeover.

But as long as Trump says none of this is happening, then for his most devout (and "devout" is the right word - as he is more popular in some quarters than that old pansy, Jesus, who spouts ridiculous liberal nonsense about 'turning the other cheek') followers, it's not happening.

As a psychologist who has done several hundred evaluations of people with strokes, traumatic brain injuries and other conditions leading to cognitive deterioration, I - along with at least 1000 other psychologists and psychiatrists - see clearly that Trump's mental faculties are rapidly deteriorating.

But all he has to say is, "I'm the smartest guy in the country," and it's true.

I'll leave you with this.

*****

The Pope was on a plane with Donald Trump. At one point on the trip, the pilot announced that, not only had they found a hippie stowed away on the plane, but the engine was failing and they should evacuate. And there are only three parachutes.

The pilot got his parachute and jumped out.

The Pope then said to Trump and the hippie, "Listen you two are younger than me, you should take the two remaining parachutes."

At that, Trump said, "Well, I'm the smartest guy in the world and only I can save the world." He grabbed the nearest parachute and jumped out."

The hippie then said to the Pope, "Don't worry, there's still two parachutes left. The smartest guy in the world just grabbed my backpack."