The future according to longtermism

Or how to sacrifice the present for the most crackbrained idea of a future

It started as a fringe philosophical theory about humanity’s future. By now it is richly funded and gaining alarming levels of influence. Called “longtermism,” it is one of the main “cause areas” of the Effective Altruism (EA) movement — a movement lead by an overwhelmingly white male group based largely out of Oxford University and Silicon Valley — which now boasts a mind-boggling $46 billion in committed funding.

EA is currently being scrutinized due to its association with Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto scandal — a case of altruistic greed gone predictably wrong — but what matters more is how this ideology is now driving research in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). EA is defined by the Center for Effective Altruism as “an intellectual project, using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible.” And “evidence and reason” have led many Effective Altruists (EAs) to conclude that the most pressing problem in the world is preventing an apocalypse where an “artificially generally intelligent” being created by humans exterminates us. Since, according to EAs, Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is likely inevitable, their goal is to make it beneficial to humanity. (Good luck with that.)

One of the most notable examples of EA’s influence comes from OpenAI, founded in 2015 by Silicon Valley elites that include Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, who committed $1 billion with a mission to “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.” Both billionaires have also heavily invested in similar initiatives to build a “beneficial” AGI, such as DeepMind (which is part of Google’s umbrella company Alphabet Inc.) and the Machine Intelligence Research Institute. Five years after its founding, OpenAI released, as part of its quest to build a “beneficial” AGI, a large language model (LLM) called GPT-3. LLMs are models trained on vast amounts of text data, with the goal of predicting probable sequences of words. This release set off a race to build larger and larger language models. In 2021, Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell, among other collaborators, wrote about the dangers of this race to the bottom in a peer-reviewed paper that resulted in their highly publicized firing from Google.

Since then, as Gebru writes in a recent Wired piece, the quest to proliferate larger and larger language models has accelerated, and many of the dangers the authors of the aforesaid paper warned about — such as outputting hateful text and disinformation en masse — continue to unfold. A few days before Gebru wrote her piece, Meta (formerly Facebook) released its “Galactica” LLM, which is purported to “summarize academic papers, solve math problems, generate Wiki articles, write scientific code, annotate molecules and proteins, and more.” Only three days later, the public demo was taken down after researchers generated “research papers and wiki entries on a wide variety of subjects ranging from the benefits of committing suicide, eating crushed glass, and antisemitism, to why homosexuals are evil.” This race hasn’t stopped at LLMs but has moved on to text-to-image models like OpenAI’s DALL-E, to which I introduced you in my last post. (The present post is in part an apology for this lapse in judgment.) The abuse potential of these text-to-image models is equally great.

As for longtermism, it might be one of the most influential ideologies that few people outside of elite universities and Silicon Valley have ever heard about. Émile P. Torres, a former longtermist who five years ago published an entire book in defense of the general idea, has come to see this worldview as “quite possibly the most dangerous secular belief system in the world today.” In an essay published last October he wrote:

over the past two decades, a small group of theorists mostly based in Oxford have been busy working out the details of a new moral worldview called longtermism, which emphasizes how our actions affect the very long-term future of the universe — thousands, millions, billions, and even trillions of years from now. This has roots in the work of Nick Bostrom, who founded the grandiosely named Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) in 2005, and Nick Beckstead, a research associate at FHI and a programme officer at Open Philanthropy. It has been defended most publicly by the FHI philosopher Toby Ord, author of The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity (2020). ...The initial thing to notice is that longtermism, as proposed by Bostrom and Beckstead, is not equivalent to “caring about the long term” or “valuing the wellbeing of future generations.” It goes way beyond this.

In other words, there is tragic, and then there is TRAGIC.

So, on the one hand, a catastrophe that reduces the human population to zero would be tragic because of all the suffering it would inflict upon those alive at the time. Imagine the horror of starving to death in subfreezing temperatures, under pitch-black skies at noon, for years or decades after a thermonuclear war. This is the first tragedy, a personal tragedy for those directly affected. But there is, longtermists would argue, a second tragedy that is astronomically worse than the first, arising from the fact that our extinction would permanently foreclose what could be an extremely long and prosperous future over the next, say, ~10^100 years. In doing this, it would irreversibly destroy the “vast and glorious” longterm potential of humanity, in Ord’s almost religious language — a “potential” so huge ... that the first tragedy would utterly pale in comparison....

To summarise these ideas so far, humanity has a “potential” of its own, one that transcends the potentials of each individual person, and failing to realise this potential would be ... a moral catastrophe of literally cosmic proportions. This is the central dogma of longtermism: nothing matters more, ethically speaking, than fulfilling our potential as a species of “Earth-originating intelligent life.” It matters so much that longtermists have even coined the scary-sounding term “existential risk” for any possibility of our potential being destroyed, and “existential catastrophe” for any event that actually destroys this potential.... If one takes a cosmic view of the situation, even a climate catastrophe that cuts the human population by 75 per cent for the next two millennia will, in the grand scheme of things, be nothing more than a small blip — the equivalent of a 90-year-old man having stubbed his toe when he was two.

The notion of “the greater good” has been used to “justify” many atrocities. As the philosopher Thomas Nagel1 wrote,

Once the door is opened to calculations of utility and national interest, the usual speculations about the future of freedom, peace, and economic prosperity can be brought to bear to ease the consciences of those responsible for a certain number of charred babies.

Imagine, then, what might be “justified” if the “greater good” isn’t national security but the cosmic potential of Earth-originating intelligent life over the coming trillions of years? Compare the number of civilians that perished during the Second World War — some 40 million — to the 10^54 or more (in Bostrom’s estimate) who could come to exist if we can avoid an existential catastrophe. What shouldn’t we do to ensure that these unborn people come to exist?

What longtermists mean by the “longterm potential of humanity” can be analyzed into three components: transhumanism, space expansionism, and a moral philosophy closely associated with what philosophers call “total utilitarianism.”

Transhumanism refers to the idea that we should use advanced technologies to reengineer our bodies and brains to create a “superior” race of radically enhanced posthumans (which, confusingly, longtermists place within the category of “humanity”). Transhumanists claim that there are various posthuman modes of being that are far better than our current human mode. We could, for instance, genetically alter ourselves to gain perfect control over our emotions ... or upload our minds to computer hardware to achieve “digital immortality.” As Bostrom put it in 2012, “the permanent foreclosure of any possibility of this kind of transformative change of human biological nature may itself constitute an existential catastrophe.”

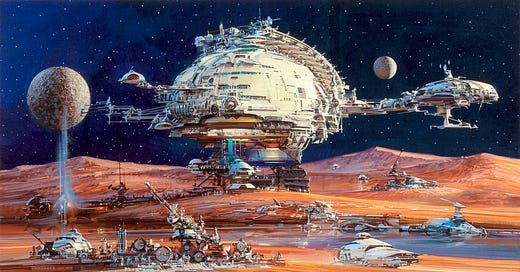

Space expansionism refers to the idea that we must colonize as much of the theoretically accessible universe as possible. Longtermists refer to the huge quantity of exploitable resources it contains as our “cosmic endowment” of negentropy. The Milky Way alone encompasses more than 100 billion stars, most with their own planets. By spreading just six light years at a time, Ord writes, our posthuman descendants could reach all the stars of our galaxy and eventually fill the entire galaxy with life. (Do we really need to inflict ourselves on the whole galaxy?)

Total utilitarianism, finally, is an ethical theory that specifies our sole moral obligation as being to maximize the total amount of “intrinsic value” in the universe. What this does not mean is that people — individuals like you and I — have any inherent value of their own. As “containers” of value we matter only insofar as we contain value. Instead of the traditional view that value exists for the sake of benefitting people, people exist for the sake of maximizing value. The more people there are with net-positive amounts of value — which is usually equated with pleasure — the better the universe will become, morally speaking.

“Technological maturity,” Torres points out, “is the linchpin here because controlling nature and increasing economic productivity to the absolute physical limits are ostensibly necessary for creating the maximum quantity of ‘value’ within our future light cone” (i.e., the part of the universe that is potentially accessible to us). According to Bostrom, the entire Universe is there for the plundering, to be manipulated, transformed and converted into “value-structures, such as sentient beings living worthwhile lives” in vast computer simulations. Yet this Baconian view, as Torres reminds us, “is one of the most fundamental root causes of the unprecedented environmental crisis that now threatens to destroy large regions of the biosphere, indigenous communities around the world, and perhaps even Western technological civilisation itself.”

On a longtermist view, every problem arises from too little rather than too much technology. In reality, as history shows and technological projections affirm, more technology equals greater risk. The longtermist answer to this conundrum is the so-called “value-neutrality thesis.” This states that technology is a morally neutral object — i.e., “just a tool.” The idea is most infamously encapsulated in the (USA’s) National Rifle Association’s slogan “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” By this logic, our best bet might be to eliminate not guns but people. To maximize the intrinsic value of the universe, we might have to take ourselves out of the equation.

Here is how Jim Stewartson has summed up longtermism:

the people pushing this idea are the ones who want to decide what our glorious future should be, and are also the ones who benefit from the people in the present “sacrificing for future generations.” Elon Musk is the ultimate metastasis of this idea. A guy with basically unlimited money who genuinely believes that the “long term” future of humanity is in space. Musk believes that any action he takes to get us closer to that reality is justified, including propping up genocidal dictator Vladimir Putin because Musk sees him as destructive to the status quo, and therefore a positive force in the world, regardless of whatever atrocities Putin commits in the process. Longtermism is just intellectualized sociopathy.

A salient feature of the mindset of which longtermism is a particularly egregious outgrowth, is its failure to see human consciousness in the context of evolution. It projects the human mind and its way of perceiving, thinking about, and acting in the world into the most distant future that it can conceive, completely ignorant of the fact that mind is an instrumental and (in evolutionary terms) transitional consciousness. Ethics or moral reasoning in particular — the valuation of things in terms of good and evil — is a necessity for a consciousness that lacks any true sense of the infinite Quality/Value/Delight at the heart of Reality, a consciousness that dwells in the distinctions it serves to create, lacking any true sense of the fundamental oneness of Reality, whether in its aspect of a single world-containing Consciousness or in its aspect of a single world-constituting Substance. The ethical standpoint, then, as Sri Aurobindo explains, “applies only to a temporary though all-important passage from one universality to another” [LD 104–105]:

In other words, ethics is a stage in evolution. That which is common to all stages is the urge of Sachchidananda towards self-expression. This urge is at first non-ethical, then infra-ethical in the animal, then in the intelligent animal even anti-ethical for it permits us to approve hurt done to others which we disapprove when done to ourselves. In this respect man even now is only half-ethical. And just as all below us is infra-ethical, so there may be that above us whither we shall eventually arrive, which is supra-ethical, has no need of ethics. The ethical impulse and attitude, so all-important to humanity, is a means by which it struggles out of the lower harmony and universality based upon inconscience and broken up by Life into individual discords towards a higher harmony and universality based upon conscient oneness with all existences. Arriving at that goal, this means will no longer be necessary or even possible, since the qualities and oppositions on which it depends will naturally dissolve and disappear in the final reconciliation. [LD 104]

To form higher and higher temporary standards as long as they are needed is to serve the Divine in his world march; to erect rigidly an absolute standard is to attempt the erection of a barrier against the eternal waters in their onflow. Once the nature-bound soul realises this truth, it is delivered from the duality of good and evil. For good is all that helps the individual and the world towards their divine fullness, and evil is all that retards or breaks up that increasing perfection. But since the perfection is progressive, evolutive in Time, good and evil are also shifting quantities and change from time to time their meaning and value. This thing which is evil now and in its present shape must be abandoned was once helpful and necessary to the general and individual progress. That other thing which we now regard as evil may well become in another form and arrangement an element in some future perfection. And on the spiritual level we transcend even this distinction; for we discover the purpose and divine utility of all these things that we call good and evil. Then have we to reject the falsehood in them and all that is distorted, ignorant and obscure in that which is called good no less than in that which is called evil. [SY 191]

It is important here not to stop after the penultimate sentence. Theologians have cooked up the most cockamamie stories to justify God’s permission (if not creation) of what we regard as evil. And in a certain sense, though certainly not in the details, they were right:

There is, no doubt, a key in the divine reason that would justify things as they are by revealing their right significance and true secret as other, subtler, deeper than their outward meaning and phenomenal appearance which is all that can normally be caught by our present intelligence: but ...

And here comes the crucial proviso —

we cannot be content with that belief, to search for and find the spiritual key of things is the law of our being. The sign of the finding is not a philosophic intellectual recognition and a resigned or sage acceptance of things as they are because of some divine sense and purpose in them which is beyond us; the real sign is an elevation towards the spiritual knowledge and power which will transform the law and phenomena and external forms of our life nearer to a true image of that divine sense and purpose. [LD 411–412]

This “elevation towards the spiritual knowledge and power which will transform the law and phenomena and external forms of our life” — in other words, the evolution of a supramental consciousness and power — is what all future extrapolations of our accumulated mental experience miss. Evolution is far from finished. When life emerged, what essentially emerged was the power to execute creative ideas. When mind emerged, what essentially emerged was the power to generate creative ideas. What has yet to emerge is the power to cast the infinite Quality/Value/Delight at the heart of reality into creative ideas, using mind to shape them and life to realize them in a world of finite forms. And when this happens, in a future distant but not nearly as distant as that contemplated by longtermists, Creation — i.e., the development of infinite Quality into finite Form — will be conscious and deliberate.

We tend to conceive of the evolution of consciousness, if not as a sudden lighting up of the bulb of sentience, then as a progressive emergence of ways of experiencing a world that exists independently of being experienced. There is no such world. There are only different ways in which One Reality manifests the world to itself — or manifests itself to itself as a world.

Our very concepts of space, time, and matter are bound up with our present mental consciousness. This made it possible to integrate the location-bound outlook of an earlier form of human consciousness into a seemingly subject-free world of three-dimensional objects. Matter as we know it was the result. It is therefore not matter that has created consciousness; it is consciousness that has created matter, first by a self-concealment or involution in an apparent multitude of formless particles, and once again by evolving our present manner of experiencing the world. Ahead lies the evolution of a consciousness — and thereby of a world — that transcends our time- and space-bound perspectives. And just as the mythological thinking of an earlier form of consciousness could not foresee the technological explosion made possible by science, so science-based thinking cannot foresee the consequences of the birth of a new world, brought about not by technological means but by the emergence of a supramental consciousness that is still involved in mind, as mind had been involved in life and life in matter.

A final word regarding value. To the separatist outlook of our present mental consciousness, where each thing, each life, each mind is fundamentally distinct from every other thing, life, or mind, the following is emblematic: All comes from dust and to dust it returns (Ecclesiastes 3:20). On this view, what is ultimately real where the material world is concerned, is a multitude of entities lacking intrinsic quality or value. To the undivided outlook of a supramental consciousness, on the other hand, the following is emblematic: From Delight all these beings are born, by Delight they exist and grow, to Delight they return (Taittiriya Upanishad 3:6). Here we are not containers of a specious and expendable kind of value. Each thing or life or mind is at its core an instance of the Delight which is the very essence of Reality and the ether in which we dwell: For who could live or breathe if there were not this delight of existence as the ether in which we dwell? (Taittiriya Upanishad 2:7). If this isn’t obvious yet it is because in this Houdiniesque manifestation which is our universe all things are struggling — both individually and collectively — to regain the means and capabilities for experiencing and expressing That Delight, tadvanam (Kena Upanishad 4:6).

Further reading (longtermism)

Longtermism, or How to Get-Out-Of-Caring While Feeling Moral and Smart, by By Jon Shaffer, PESTE Magazine, October 10, 2022.

Understanding “longtermism”: Why this suddenly influential philosophy is so toxic, by Émile P. Torres, Salon, August 20, 2022.

How ‘Longtermism’ Is Helping the Tech Elite Justify Ruining the World, by Rohitha Naraharisetty, The Swaddle, September 5, 2022.

“Longtermism” Movement Misses the Importance of War, by John Horgan, Scientific American, September 28, 2022.

What “longtermism” gets wrong about climate change, by Émile P. Torres, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 22, 2022.

Further reading (Aurocafe)

T. Nagel, War and Massacre, Philosophy and Public Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 2 (Winter 1972), 123–144.

The “value neutrality” thesis has been discredited for over 60 years. Despite some fruitless attempts by Habermas, it was killed by the critique of the role technology plays in modern society by the Frankfurt School, Critical Theory in general, and by Herbert Marcuse in particular. Not to mention Ellul or Mumford well before that time. There is a well presented summary of the 60s debate in one of Feenberg’s early studies, called “Alternative Modernity” (U of C Press, 1995). He went on to far greater depths after this.

In any case, what we face today is what Foucault called “the major enemy”: universal fascism. Nothing more, nothing less. Until we start to understand the power relations of this monstrosity, there is little hope of redeeming ourselves and liberate us from “desiring the very things that dominate and exploit us”.

Amongst them, I’d say we should avoid grappling with the elusive, and dangerously toxic idea of “evolution”, which more often than not ends in the well known paths of Taylorism (E.B.) , Eugenics, Sociobiology and this new form of anthropogenic minimalism called “Longtermism”, whatever that is. It all sounds so plausible “to us” (once you ignore pretty much everything, of course), that’s why it keeps coming back.

When the Ngaju of South Borneo placed a corpse in a coffin that was built in the shape of a boat, this was neither a coffin nor a boat. It was a hornbill or a watersnake, it “was” the godhead, it “was” the Tree of Life and the primeval mountain. There was no representation of it, neither act of evolution, because the act was unboundedly creative, or more precisely “re-creative”. The only evolution that exists is that which has no limits. Nicholas of Cusa’s infinite circle, whose circumference is nowhere and centre is everywhere. (On Learned Ignorance, 1.Ch 20). This happens here and now. Nowhere else.