To Schrödinger, the agreement between the contents of our respective “spheres of consciousness” was not rationally comprehensible. “In order to grasp it,” he wrote,1 “we are reduced to two irrational, mystical hypotheses.” One of them was “the so-called hypothesis of the real external world,” which postulates “a real world of bodies which are the causes of sense-impressions and produce roughly the same impression on everybody.” This he rejected, and for good reason. He would have agreed with Niels Bohr as well as the QBists about the role that language plays in establishing the correspondence between “the content of any one sphere of consciousness and any other, so far as the external world is concerned.” What did establish it for him was

language, including everything in the way of expression, gesture, taking hold of another person, pointing with one's finger and so forth, though none of this breaks through that inexorable, absolute division between spheres of consciousness.

But Schrödinger also made it clear that establishing something is not the same as accounting for it. And indeed, if the shapes of things resolve themselves into reflexive spatial relations entertained by a single Being or Substance, then there has to be more to the agreement between the content of one sphere of consciousness and another than is warranted by language.

To Schrödinger, what actually accounts for the agreement between our respective spheres of consciousness is that “we are all really only various aspects of the One.” The “arithmetical paradox” posed by the experience of one world by many individual subjects has only one solution,2 to wit:

the unification of minds or consciousnesses. Their multiplicity is only apparent, in truth there is only one mind. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads. And not only of the Upanishads.

Elsewhere he refers to it as “the Eastern doctrine of identity.” The One invoked by Schrödinger is the Ultimate Subject from which we are separated by a veil of self-oblivion. The same veil, according to the Upanishads, also prevents us from perceiving the Ultimate Object, as well as its fundamental identity with the Ultimate Subject. It prevents us from perceiving that the world is something that the One (as Ultimate Object) manifests to itself (as Ultimate Subject) — and therefore to us who are but “various aspects of the One.”

Schrödinger, too, appears to have missed that identity. Believing that we perceive the same world because we are ultimately the same subject, he (sometimes) arrives at something like Bishop Berkeley’s idealism.3 (Note that “representation” is a woefully inadequate translation of Vorstellung. A Vorstellung is something the mind presents — not re-presents — to itself.)

[To say] that the becoming of the world is reflected in a conscious mind is but a cliché, a phrase, a metaphor that has become familiar to us. The world is given but once. Nothing is reflected. The original and the mirror-image are identical. The world extended in space and time is but our representation (Vorstellung). Experience does not give us the slightest clue of its being anything besides that — as Berkeley was well aware.

Actually it does give us such a clue, for the quantum-mechanical correlations between outcome-indicating events warrant the conclusion that the shapes of things resolve themselves into reflexive spatial relations entertained by a single Being or Substance. Beyond the so-called classical domain, which is accessible to sensory experience and therefore capable of being described in terms of concepts that owe their meanings to the spatiotemporal structure of human sensory experience,4 there is a so-called quantum domain, which is not accessible to human sensory experience and therefore cannot be expected to be describable by means of such concepts.

To Bohr, the physical content of quantum mechanics was “exhausted by its power to formulate statistical laws governing observations obtained under conditions specified in plain language”.5 There are, however, ontological conclusions that can be drawn from these laws. And one of them is that the shapes of things resolve themselves into reflexive relations entertained by a single Substance. Schrödinger, too, failed to draw this conclusion, in spite of his warning6 that

[o]ur modern atoms, the ultimate particles, must no longer be regarded as identifiable individuals. This is a stronger deviation from the original idea of an atom than anybody had ever contemplated. We must be prepared for anything.

Schrödinger has often been portrayed as a realist about wave functions. While this was true of the Schrödinger of 1926, it does not apply to the Schrödinger post 1926, who (sometimes) adopted a downright postmodernist stance.7 This is from a 1950 lecture8:

we do give a complete description, continuous in space and time without leaving any gaps, conforming to the classical ideal — a description of something. But we do not claim that this “something” is the observed or observable facts; and still less do we claim that we thus describe what nature (matter, radiation, etc.) really is. In fact we use this picture (the so-called wave picture) in full knowledge that it is neither.

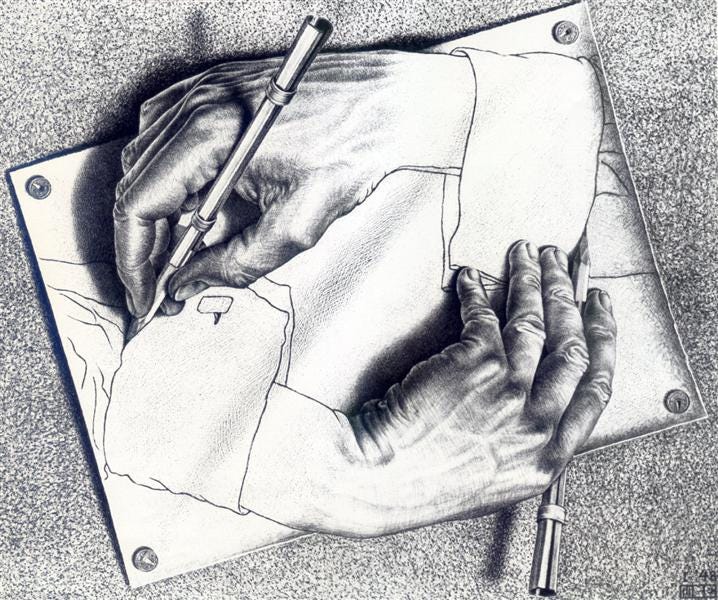

Needless to say, when I say that the shapes of things resolve themselves into reflexive relations entertained by a single substance, the word “substance” cannot have the Lockean sense of a collection of empirical properties which constantly go together, nor can it have the Kantian sense of a bundle of sensible impressions that we can think of as self-existent — and even should, for “otherwise there would follow the absurd proposition that there is an appearance without anything that appears”.9 There are no self-existent objects. Because atoms and subatomic particles belong to the quantum domain, they owe their properties — and even their existence as individual quantum objects — to the experimental conditions under which they are observed. t follows that the objects belonging to the classical domain cannot be reductively explained in terms of the objects that populate the quantum domain. This mutual dependence of the two domains is reminiscent of M.C. Escher’s famous Drawing Hands.

The circularity present in this drawing can be resolved by realizing that the actual drawing hand is neither of the two hands in the drawing. The reciprocal dependence of classical and quantum objects, or of the classical and quantum domains, can be similarly resolved by realizing that neither kind of object or domain is sufficient to account for itself or the other. Both depend on a tertium quid, which to my mind is best characterized by the Upanishadic term saccidānanda, which is the ligated form of the three terms sat, cit, and ānanda.

In the view of the Upanishads, what ultimately exists is at once the ultimate substance that constitutes things (sat), the ultimate consciousness that contains things (cit), and an infinite quality/delight (ānanda) that experiences and expresses itself in things. In other words, the world is something that the One as the ultimate object (sat) manifests to itself as the ultimate subject (chit).

If we all perceive the same world, it is not only because ultimately we are all the same subject but also because the ultimate constituents of things are identical in the strong sense of numerical identity. The proper term to describe the transition from the unity of this Ultimate Constituent to the multiplicity of the macroscopic world is manifestation, and since subatomic particles, non-visualizable atoms, and partly visualizable molecules mark the various stages of this transition, the essential difference between the classical domain and the quantum domain is the difference between the manifested world and its manifestation. Instead of being constituent parts of the manifested world, the objects that populate the quantum domain are instrumental in the manifestation of the classical domain.

Across the stages of this transition, the differentiatedness of the manifested world — its being divided into distinguishable regions of space, distinguishable objects, and distinguishable properties — is gradually realized. There is a stage at which the One presents itself as a multitude of formless particles. This stage is probed by high-energy physics and described in terms of transition probabilities between the in-states and out-states of particles in scattering experiments. There are stages that mark the emergence of form, albeit as a type of form that cannot as yet be visualized. The forms of nucleons, nuclei, and atoms can only be mathematically described, as probability distributions over abstract spaces of increasingly higher dimensions. At energies low enough for atoms to be stable, there emerge objects with fixed numbers of components, and these can be described in terms of statistical correlations between the possible outcomes of measurements. But it is only at the penultimate stage that there are objects — namely, molecules — whose primary structures can be visualized.

The dependence of the manifested world on what is instrumental in its manifestation can be encapsulated in an exceedingly concise creation story:

By entering into reflexive spatial relations, the One gives rise to (i) what looks like a multiplicity of relata if the reflexive quality of the relations is ignored, and (ii) what looks like a substantial expanse if the spatial quality of the relations is reified.

Differently put:

By entering into reflexive relations, the One creates both matter and space, for space may be defined as the totality of existing spatial relations, while matter may be defined as the corresponding (apparent) multitude of relata.

Because the relations are reflexive, the multiplicity of the corresponding relata is apparent rather than real. Does this mean that the world is unreal, as Shankara and other illusionist philosophers have contended? By no means, for the world owes its existence to a multitude of reflexive relations, and this is real.

What about the dependence of what is instrumental in the world’s manifestation on what happens or is the case in the manifested world? Here the relevant question to ask is: how are we to describe the intermediate stages of the manifestation, the stages at which the distinguishability of regions of space, of objects, and of properties is as yet incompletely realized? The answer to this question is that whatever is not intrinsically distinct can only be described in terms of probability distributions over events that are intrinsically distinct, namely, the possible outcomes of measurements. What is instrumental in the manifestation of the world can only be described in terms of correlations between events that happen (or could happen) in the manifested world. Incidentally, this also goes a long way towards explaining why the general theoretical framework of contemporary physics is a probability calculus, and why the events to which it serves to assign probabilities are measurement outcomes, which is no mean achievement.

But how do we account for the intrinsic distinctness of measurement outcomes? This takes us back to our tertium quid. Since the One manifests the world to itself, and since we are “really only various aspects of the One,” it also manifests the world to us, in our experience, where the different possible outcomes of a measurement are indicated by different possible experiences. Measurement outcomes are intrinsically distinct because different experiences are tautologically distinct.

The question may be asked, how does the world manifested to us differ from the world manifested to the Ultimate Subject? Forgetting about the colossal difference between an aperspectival consciousness and a perspectival one, one may be tempted to identify the world experienced by the Ultimate Subject with the world as it really is. But this fails to do justice to the evolutionary character of the world.

We tend to conceive of the evolution of consciousness as a progressive emergence of ways of experiencing a world that exists in itself, independently of being experienced. But the world is what it is only because it is experienced the way it is experienced. While there is no world that exists in itself, there are different ways in which the world is experienced. According to Jean Gebser,10 who has painstakingly described and documented each of the structures of consciousness that has emerged or is in the process of emerging, the principal characteristic of a consciousness structure is its dimensionality.

Evolution thus has two aspects, to say the least: the biological evolution of organisms as seen and understood by our present, mental consciousness structure, and the successive emergence of consciousness structures of increasing dimensionality and the consequent increase in the dimensionality of the experienced/manifested world.

Gebser refers to the aperspectival consciousness structure as integral because it integrates the emerging consciousness structures and their world experiences into a single world experience, which Sri Aurobindo calls supramental. As we, presently, look at evolution from a static, unchanging vintage point, so does the supramental consciousness. The difference is that our static outlook is hitched to a particular consciousness structure (which makes it possible for us to ignore the world’s dependence on the consciousness by which it is experienced), whereas the supramental outlook is static in that it encompasses all consciousness structures in an integral totality and therefore transcends the flow of time.

We may be able to grasp in the abstract a future experience in which the dimensionality of the world exceeds that of the world as we presently experience it. But this is the least of it, for what a supramental consciousness experiences it creates — it causes to be. This cannot mean that it will change the world as it is in itself, for (once again) there is no world that exists in itself, out of relation to consciousness. It means that the evolutionary emergence of the supramental consciousness will change the world in the most objective way possible, i.e., it will have a transformative effect on the world experienced by a mental consciousness and perhaps even a submental one.

The manifestation of the world is therefore something in which the evolving consciousness will increasingly participate. To a mental consciousness there is a significant difference between what the world is and what it should be. To a supramental consciousness, the world is at every moment what it should be. None of the scientific or technological shenanigans of our mental consciousness will cause the world to be what it should be. Only by the evolution of a supramental consciousness can the world become what it should be, and this not only to those who are conscious in the supramental way but also to those who remain conscious in the mental or a submental way. It would be futile to ask whether the eventual abolition of falsehood and evil will be so objective as to be real even to an unchanged consciousness, for ultimately there will be no one whose consciousness will be left unchanged.

Our difficulty in comprehending how everything can be as it should be, has a counterpart in the supramental experience of the world: it fails to comprehend how the world can be as it is seen by us. On July 18, 1961,11 the Mother observed:

When one comes out of that [ordinary] consciousness and enters the Truth-Consciousness [a term for the supramental consciousness frequently used by Sri Aurobindo], one is incredulous that such things as suffering, misery and death can exist; it’s amazing, in the sense that (when one is truly on the other side) ... one doesn’t understand how all this can be happening.

And again on May 31, 196912:

But what’s this creation? … You know, separation, then wickedness, cruelty (the thirst to cause harm, we might say), then suffering, again the joy of causing suffering, and then all disease, decomposition, death — destruction. (All that is part of a single thing.) What happened? … The experience I had was the UNREALITY of those things, as though we had stepped into an unreal falsehood, and when you step out of it, everything vanishes — it DOES NOT exist, it isn’t. That’s what is frightful! What to us is so real, so concrete, so dreadful, all that does not exist.

E. Schrödinger. What is real? In My View of the World (Cambridge University Press, 1964).

E. Schrödinger, The Arithmetical Paradox: The Oneness of Mind, in: What Is Life? With: Mind and Matter & Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Op. cit.

These include substance, causality, and interaction, which are the pillars of the object-oriented language of classical discourse, as well as distance, duration, relative orientation, energy and momentum (both linear and angular).

Niels Bohr: Collected Works Vol. 10, p. 159 (Elsevier, 1999).

E. Schrödinger, Science and Humanism, in, Nature and the Greeks and Science and Humanism, pp. 103‒171 (Canto Classics, 2014).

M. Bitbol, Schrödinger’s Philosophy of Quantum Mechanics, p. 25 (Kluwer, 1996).

Op. cit.

I. Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, p. 115 (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

J. Gebser. The Ever-Present Origin (Ohio University Press, 1986).

Op. cit. Vol. 02.

Op. cit. Vol. 10.

Here again, to appreciate your continued efforts not allowing “sleeping monsters lie”, not for a day, not for a forthright. The monster is evil, it is deep and mysterious, but as Borges reminded us, at the same time is white and beautiful, like Moby-Dick.

“And one may wonder too that generations of scholars have left such an ultimate submission of reason to unaccountable decisions unchallenged. Perhaps both Kant and his successors instinctively preferred to let such sleeping monsters lie, for fear that, once awakened, they might destroy their fundamental conception of knowledge. For, once you face up to the ubiquitous controlling position of unformalizable mental skills, you do meet difficulties for the justification of knowledge that cannot be disposed of within the framework of rationalism.”

(Michael Polanyi, “The Unaccountable Element is Science”, Knowing and Being, p. 106)

Schrödinger was right when he said that the original and the mirror image are identical. But they are identical not because they have form, they are identical because they do not have it. The problem, which as stated is derived from a linguistic misrepresentation, stems from the fact that (generically speaking) we in the West tend to identify the concrete, the original, with that which has shape, that which bears extensive relations. What we can only re-present is not concrete, is entirely abstract. Whitehead understood this misplaced fallacy better than anyone (probably not better than The Mother, I might adventure to say). That which is knowable to us moves in the opposite direction, it lies in the “absolute near side”. The fruits of scientific knowledge, magnificent as they are, end up in one point and one point only: “We got hold of the entirely abstract, and we triumphed”. That’s the ultimate price. The concrete remains not only untouched, but tragically disregarded. Jung panicked at this ominous perspective, Kierkegaard suffered for it; and their fears have been entirely justified.

Btw, what that “tertium quid” shows us, that platonic “triton genos” which accounts for the existence of distinct experiences, if anything, is that the One is entirely active, in a sense it is pure activity and nothing less.

Brilliant! Thank you!