Western thought in need of “a bit of blood-transfusion from Eastern thought”

A brief examination of Schrödinger’s views on consciousness in light of Sri Aurobindo’s writings

As we have seen on several occasions, Erwin Schrödinger believed that “our present way of thinking does need to be amended, perhaps by a bit of blood-transfusion from Eastern thought” [AP1]. While his thoughts on “the Eastern doctrine of identity” [AP] or “the doctrine of the Upanishads” [AP] are remarkable, they obviously are no match for Sri Aurobindo’s understanding of these subjects. It will therefore be worth our while to examine the extent to which Schrödinger’s thinking agrees with Sri Aurobindo’s insight.

Schrödinger was keenly aware of the mind’s “curious double role” [AP], which Edmund Husserl2 referred to as “the paradox of human subjectivity” (“being a subject for the world and at the same time being an object in the world”):

On the one hand [mind] is the stage, and the only stage on which this whole world-process takes place, or the vessel or container that contains it all and outside which there is nothing. On the other hand we gather the impression, maybe the deceptive impression, that within this world-bustle the conscious mind is tied up with certain very particular organs. [AP]

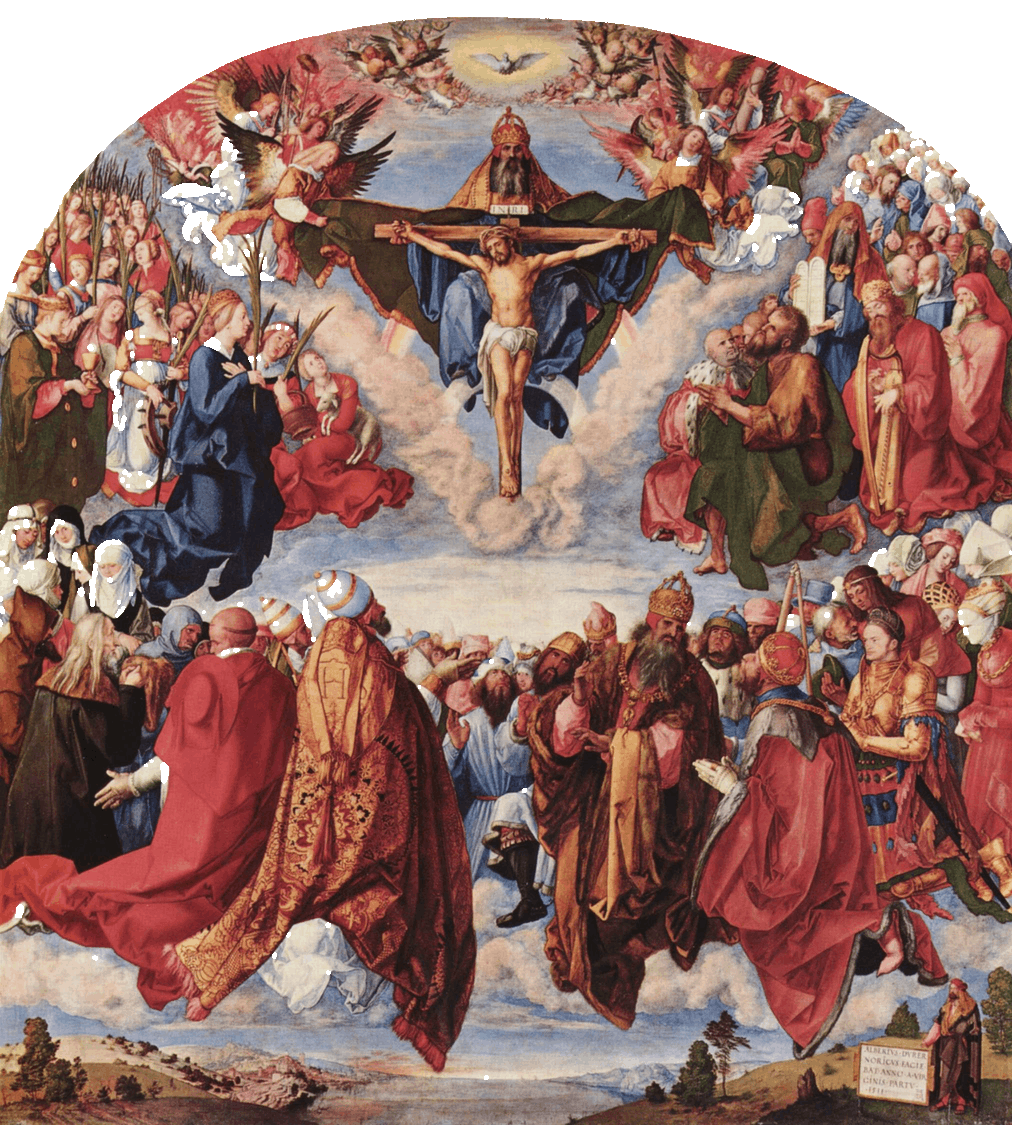

To Schrödinger, “the best simile of the bewildering double role of mind” was that of a painter or poet who introduces into his work “an unpretending subordinate character who is himself” — the blind bard in Homer’s Odyssey who is Homer, the humble side-figure in Albrecht Dürer’s All-Saints painting who is Dürer himself: “On the one hand mind is the artist who has produced the whole; in the accomplished work, however, it is but an insignificant accessory that might be absent without detracting from the total effect.”

But something in Schrödinger’s simile is missing; something is not quite right; something distorts the actual facts of the matter. What is missing is the all-important distinction between an aperspectival consciousness, which experiences the world from no particular location or from everywhere at once, which may indeed be described as the vessel that “contains it all,” and a perspectival consciousness, which experiences the world from a multitude of locations within the world. To facilitate this distinction, Sri Aurobindo has coined the term “supermind” for the former, reserving “mind” for the latter.

While Schrödinger conflates the mental with the supramental experience of space, he misses the supramental experience of time. According to him, “mind is always now. There is really no before and after for mind. There is only a now that includes memories and expectations.” [AP] While it is true that the mind is located in the temporal present, capable of reaching into the past or the future only by way of memory or expectation, the same is not true of the supermind. As Sri Aurobindo3 explains, “[t]ime is for the Mind a mobile extension measured out by the succession of the past, present and future in which Mind places itself at a certain standpoint whence it looks before and after” [LD 142–143]. Similarly, space is “measured out by divisibility of substance; at a certain point in that divisible extension Mind places itself and regards the disposition of substance around it” [LD 143]. Supermind, on the other hand, encompasses both time and space:

to a consciousness higher than Mind which should regard our past, present and future in one view, containing and not contained in them, not situated at a particular moment of Time for its point of prospection, Time might well offer itself as an eternal present. And to the same consciousness not situated at any particular point of Space, but containing all points and regions in itself, Space also might well offer itself as a subjective and indivisible extension,—no less subjective than Time. At certain moments we become aware of such an indivisible regard upholding by its immutable self-conscious unity the variations of the universe. But we must not now ask how the contents of Time and Space would present themselves there in their transcendent truth; for this our mind cannot conceive,—and it is even ready to deny to this Indivisible any possibility of knowing the world in any other way than that of our mind and senses. [LD 144]

The difference between the aperspectival view of space and our own is underscored by the fact that the familiar dimensions of space — viewer-centered depth and lateral extent — only come into being when the One adopts a multitude of localized standpoints. Once the world is viewed in perspective, objects are seen from outside, i.e., all that is ever seen is their surfaces.

Richard Feynman4 tells the story of his sitting in on a philosophy seminar on Whitehead’s Process and Reality and being asked by the instructor whether he thought that an electron was an “essential object”:

Well, now I was in trouble. I admitted that I hadn’t read the book, so I had no idea of what Whitehead meant by the phrase; I had only come to watch. “But,” I said, “I’ll try to answer the professor’s question if you will first answer a question from me, so I can have a better idea of what ‘essential object’ means. Is a brick an essential object?”

What I had intended to do was to find out whether they thought theoretical constructs were essential objects. The electron is a theory that we use; it is so useful in understanding the way nature works that we can almost call it real. I wanted to make the idea of a theory clear by analogy. In the case of the brick, my next question was going to be, “What about the inside of the brick?” and I would then point out that no one has ever seen the inside of a brick. Every time you break the brick, you only see the surface. That the brick has an inside is a simple theory which helps us understand things better.

Or perhaps not truly understand them, for the true insides of things — those not hidden behind surfaces — are only accessible to an aperspectival consciousness.

Once the distinction is made between mind and supermind, the question arises as to how these two poises of consciousness are related. The key to understanding this is the concept of involution. If the One adopts a multitude of localized standpoints, knowledge by identity takes the form of direct knowledge: each individual knows the others directly, without mediating representations. There is as yet no ignorance in the Vedantic sense of avidya; the experience of the many by the many remains part of the experience of the One by the One. Avidya becomes a reality when the One identifies itself with each localized standpoint to the exclusion of all others. Then the surfaces of things are all that is seen; the conscious selves and essential qualities of things are not perceived. Then “you can stare at someone’s brain from dawn till dusk and you will not perceive the consciousness that is so apparent to the person whose brain you are so rudely eyeballing,” as the philosopher Colin McGinn5 rather graphically put it.

Schrödinger put his finger on the problem, yet by conflating those two poises of consciousness he also rendered it insoluble. To him the problem was that “our science — Greek science — is based on objectivation, whereby it has cut itself off from an adequate understanding of the Subject of Cognizance, of the mind.” [AP] In another essay6 he wrote:

Without being aware of it and without being rigorously systematic about it, we exclude the Subject of Cognizance from the domain of nature that we endeavour to understand. We step with our own person back into the part of an onlooker who does not belong to the world, which by this very procedure becomes an objective world. [PO]

The mental procedure of objectivation has a spiritual counterpart in the transition from the primary, comprehending poise to the secondary, apprehending poise of supermind, but it corresponds to only one of the steps involved:

[W]hat then is the origin of mentality and the organisation of this lower consciousness in the triple terms of Mind, Life and Matter which is our view of the universe? For since all things that exist must proceed from the action of the all-efficient Supermind ... there must be some faculty of the creative Truth-Consciousness which so operates as to cast them into these new terms, into this inferior trio of mentality, vitality and physical substance. This faculty we find in a secondary power of the creative knowledge, its power of a projecting, confronting and apprehending consciousness in which knowledge centralises itself and stands back from its works to observe them....

First of all, the Knower holds himself concentrated in knowledge as subject and regards his Force of consciousness as if continually proceeding from him into the form of himself, continually working in it, continually drawing back into himself, continually issuing forth again. From this single act of self-modification proceed all the practical distinctions upon which the relative view and the relative action of the universe is based. A practical distinction has been created between the Knower, Knowledge and the Known....

Secondly, this conscious Soul concentrated in knowledge, this Purusha observing and governing the Force that has gone forth from him, his Shakti or Prakriti, repeats himself in every form of himself.... In each form this Soul dwells with his Nature and observes himself in other forms from that artificial and practical centre of consciousness. In all it is the same Soul, the same divine Being; the multiplication of centres is only a practical act of consciousness intended to institute a play of difference, of mutuality, mutual knowledge, mutual shock of force, mutual enjoyment, a difference based upon essential unity, a unity realised on a practical basis of difference....

We can see that pursued a little farther [this new status of the all-pervading Supermind] may become truly Avidya, the great Ignorance which starts from multiplicity as the fundamental reality.... We can see also that once the individual centre is accepted as the determining standpoint, as the knower, mental sensation, mental intelligence, mental action of will and all their consequences cannot fail to come into being. [LD 149–150]

Schrödinger understands “the pandemonium of disastrous logical consequences,” which follow from “the fact that a moderately satisfying picture of the world has only been reached at the high price of taking ourselves out of the picture, stepping back into the role of a non-concerned observer.” [PO] He points out two of these consequences. The first is that our world picture lacks qualia: “Colour and sound, hot and cold are our immediate sensations; small wonder that they are lacking in a world model from which we have removed our own mental person.” The second is “our fruitless quest for the place where mind acts on matter or vice-versa”: “The material world has only been constructed at the price of taking the self, that is, mind, out of it, removing it; mind is not part of it; obviously, therefore, it can neither act on it nor be acted on by any of its parts.”

While the stuff from which our world picture is built is yielded exclusively from the sense organs as organs of the mind, so that every man’s world picture is and always remains a construct of his mind and cannot be proved to have any other existence, yet the conscious mind itself remains a stranger within that construct, it has no living space in it, you can spot it nowhere in space. [PO]

If we then reify this world picture, we are forced to carve out for our sensory qualities a living space, to “invent a new realm for them, the mind, saying that this is where they are, and forgetting the earlier part of the story”.7 “I so to speak put my own sentient self (which had constructed this world as a mental product) back into it.” [PO]

Yet these “disastrous logical consequences” only follow if the second step (the multiple localization of the subject) is ignored, and if the first step (the projection of the One qua object in front of the One qua subject) is mistaken for the mental procedure of objectivation. To Schrödinger, “[t]he reason why our sentient, percipient and thinking ego is met nowhere within our scientific world picture” is that this sentient, percipient and thinking ego “is itself that world picture. It is identical with the whole and therefore cannot be contained in it as a part of it.” [AP] This is a fine example of our finite mental logic, which fails to grasp what Sri Aurobindo calls “the logic of the Infinite.” This logic allows the One to become Many without ceasing to be One, and to be at once the continent and each part contained therein.

The Infinite is not a sum of things, it is That which is all things and more. If this logic of the Infinite contradicts the conceptions of our finite reason, it is because it exceeds it and does not base itself on the data of the limited phenomenon, but embraces the Reality and sees the truth of all phenomena in the truth of the Reality; it does not see them as separate beings, movements, names, forms, things; for that they cannot be.... [They are] realities which exist by their root of unity and, so far as they can be considered independent, are secured in their independence ... only by their perpetual dependence on their parent Infinite, their secret identity with the one Identical. The Identical is their root, their cause of form, the one power of their varying powers, their constituting substance. [LD 353–354]

The infinite multiplicity of the One and the eternal unity of the Many are the two realities or aspects of one reality on which the manifestation is founded. [LD 687]

[O]ut of the supreme being in which all is all without barrier of separative consciousness emerges the phenomenal being in which all is in each and each is in all for the play of existence with existence, consciousness with consciousness, force with force, delight with delight. This play of all in each and each in all is concealed at first from us by the mental play or the illusion of Maya which persuades each that he is in all but not all in him and that he is in all as a separated being not as a being always inseparably one with the rest of existence. [LD 124]

Schrödinger is right when he insists that “[t]he world is given to me only once, not one existing and one perceived.” [PO] But this leaves open the possibility that the world is given to different poises of consciousness, including one in which all is known to be in each, and one in which the whole appears to be nothing but a collection of separate parts.

The reason we see the whole as a collection of separate parts is the same as that which makes us think of ourselves as separate individuals. It comes into play when the One identifies itself with each localized subject to the exclusion of all other subjects. Another consequence of this exclusive concentration of the One in each of the Many is that the knowledge of other individuals ceases to be direct. The individual being can then be directly aware only of its own form. Hence it can only be indirectly aware of the forms of other individual beings. Direct knowledge is reduced to an indirect knowledge, i.e., a direct knowledge by the individual of some of its internal attributes (such as, in our case, patterns of electrochemical pulses in brains), which serve as representations of external objects.

The ambiguity of the word “representation” is a source of considerable confusion in the philosophy of mind. As used just now, it means (i) an internal object that is not experienced by the subject but which mediates the subject’s indirect experience of an external object. The other possible meaning is (ii) a subject’s experience of an internal object, which in some way is caused by an external object that is not experienced.

Schrödinger is in agreement with Sri Aurobindo in that representations in the sense of experiences caused by objects existing out of relation to any kind of consciousness can be ruled out. There are no such objects. There are only different ways in which the One manifests itself to itself. Indirect knowledge comes into play when the One manifests itself as a multitude of objects to itself as a multitude of subjects, and if each subject is exclusively identified with a single object.

This knowledge, as has been explained in a previous post, depends on two sources of information: quantitative information about the external object, which is represented by an internal object such as such as a neural firing pattern in the visual or auditory cortex, and qualitative information provided by a subliminal source, by which the quantitative information encoded in the internal object is decoded, resulting in an experience that appears to represent the external object in the second sense of “representing.” As the following diagram suggests, indirect knowledge is supported and made possible by a subliminal direct knowledge, even as direct knowledge is supported and made possible by the identity of the knower with the known.

So, there are two reasons why brains do not give rise to experiences, contrary to what most cognitive scientists and philosophers of mind believe. The first is that brains, as they are known and investigated by neuroscientists, are experiences, and experiences cannot give rise to experiences. The second is that neural representations alone cannot give rise to experiences, for it also takes intuitions provided by a subliminal interpreter of the information that brains provide. As Sri Aurobindo explains,

what we get by our sense is not the inner or intimate touch of the thing itself, but an image of it or a vibration or nerve message in ourselves through which we have to learn to know it. These means are so ineffective, so exiguous in their poverty that, if that were the whole machinery, we could know little or nothing or only achieve a great blur of confusion. But there intervenes a sense-mind intuition which seizes the suggestion of the image or vibration and equates it with the object, a vital intuition which seizes the energy or figure of power of the object through another kind of vibration created by the sense contact, and an intuition of the perceptive mind which at once forms a right idea of the object from all this evidence. [LD 547–548]

In [AP] Schrödinger asked a provocative question: “But a world existing for many millions of years without any mind being aware of it, contemplating it, is it anything at all?” To which he added that “the romance of a world that had existed for many millions of years before it, quite contingently, produced brains in which to look at itself, has an almost tragic continuation.” He described this continuation in the words of Nobel laureate Charles S. Sherrington8:

The universe of energy is we are told running down. It tends fatally toward an equilibrium which shall be final. An equilibrium in which life cannot exist. Yet life is being evolved without pause. Our planet in its surround has evolved it and is evolving it. And with it evolves mind. If mind is not an energy-system how will the running-down of the universe of energy affect it? Can it go unscathed? Always so far as we know the finite mind is attached somehow to a running energy-system. When that energy-system ceases to run what of the mind which runs with it? Will the universe which elaborated and is elaborating the finite mind then let it perish?

In the view of Sri Aurobindo, the finite mind, once transformed into supermind, will not let the ultimate fate of the universe be the heat death predicted by thermodynamics. But if we, at this early stage of the convergent evolution of our ways of seeing and being, are wrong about the future of the universe, are we not also wrong about its past, as Schrödinger appears to suggest? Considering that our knowledge of the past is based on the world as presently manifested to us and on facts and clues therein contained, the answer will obviously be negative.

What we are missing about the past is that consciousness was present from the start. That consciousness was involved (latent or dormant) for billions of years, doesn’t mean that it wasn’t there. It means that in an inanimate object consciousness lacks the instrumentation needed to give it content. Because the substance that constitutes the world is one with the consciousness that contains it, consciousness is present in all things. When the means to give it content evolve, consciousness awakens as if from a deep sleep or trance.

There are therefore two aspects to the evolution of consciousness that we must keep apart: the evolution of whatever it takes to give it content, and the awakening of consciousness by giving it content. The philosopher John Searle9 makes this very distinction when he submits that “[w]e should think of perception not as creating consciousness but as modifying a preexisting conscious field” (emphasized by Searle). He advocates that “we should think of perceptual inputs ... as producing bumps and valleys in the conscious field that has to exist prior to our having the perceptions.” A brain is what it takes to give a preexisting consciousness the content that it has. (And perhaps it takes much less than a fully fledged brain, as the example of a paramecium suggests.)

AP = E. Schrödinger, The Arithmetical Paradox: The Oneness of Mind, in: What Is Life? With: Mind and Matter & Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

E. Husserl, The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, p. 178 (Northwestern University Press, 1970).

LD = Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department, 2005).

R.P. Feynman (as told to Ralph Leighton), Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman (Bantam, 1986).

C. McGinn, The Mysterious Flame: Conscious Minds in a Material World, p. 47 (Basic Books, 1999).

PO = E. Schrödinger, The Principle of Objectivation, in: What Is Life? With: Mind and Matter & Autobiographical Sketches (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

E. Schrödinger, William James lectures (c. 1954), 3rd lecture, in: E. Schrödinger, The interpretation of quantum mechanics (Dublin seminars 1949-1955 and other unpublished texts), p. 145, edited by M. Bitbol (Ox Bow Press, 1995).

C.S. Sherrington, Man on his Nature, p. 232 (Cambridge University Press, 1940/2009).

J.R. Searle, Mind: A Brief Introduction, p. 155 (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Everything that is is as object. I have only two small objections against this, the most extraordinary of modern views. You are not and object, and you are all that is.