The quagmire known as the “block universe”

On the mindless conflation of actual events and spacetime points

In August of 2002 I received the following email from Dennis Dieks — a professor at Utrecht University, a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (since 2008), and a lead editor of the journal Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics.

Dear Dr. Mohrhoff,

I was asked to write a brief review, for the Mathematical Reviews, of your article “The world according to QM” (Found. Phys.). I was not familiar with this article, or other work of yours, before. I was much impressed by many of the arguments you put forward in the Found. Phys. article. In particular, I think your exposure of the all too often found question “how do probabilities turn into facts” as a pseudo-problem is extremely lucid. I agree with many other points as well, e.g. about the flow of time and the notion of a block universe. Of course, I also concur in the view that the introduction of consciousness in the way Stapp does it is a wholly gratuitous manoeuvre. Finally, I have great sympathy for the idea that spatiotemporal features should be regarded as properties of physical systems, rather than assuming a spacetime continuum beforehand…. I have expressed similar viewpoints in writing myself, but I think not as eloquently as you have now.

The full title of the paper in question is “The world according to quantum mechanics, or the 18 errors of Henry P. Stapp” (Foundations of Physics 32/2, 217–254, 2002). A preprint of this paper is available here.

To begin with, I need to own up to an error. In those days I still believed that the task of physics was to describe the objective world without dragging in consciousness or observers. Ever since quantum mechanics appeared on the scene, it has been argued that explaining the “collapse of the wave function” at the time of a measurement requires just that. David Mermin once characterized my views as “Just the facts, Ma'am.” To describe the objective world I thought it sufficient to describe the facts and their correlations. In quantum physics — the general theoretical framework of contemporary physics — the relevant facts are those that indicate outcomes of measurements. It took me a long time (and a little help from some friends) to realize that no outcome can be indicated in the absence of a conscious observer to whom it is indicated. Here is what I wrote:

What is a fact? The Concise Oxford Dictionary (8th edition, 1990) defines “fact” as a thing that is known to have occurred, to exist, or to be true; a datum of experience; an item of verified information; a piece of evidence. Other dictionaries give variations on the same theme. Should we conclude from this that the editors of dictionaries are idealists wanting to convince us that the existence of facts presupposes knowledge or experience? Obviously not. The correct conclusion is that “fact,” like “existence,” like “reality,” is so fundamental a concept that it simply cannot be defined. So what is the editor of a dictionary to do? The obvious thing is to fall back on the metalanguage of epistemology....

If “fact” is so fundamental a term that it cannot be defined, the existence of facts — the factuality of events or states of affairs — cannot be accounted for, any more than we can explain why there is anything at all, rather than nothing.... Before the mystery of existence — the existence of facts — we are left with nothing but sheer dumbfoundment. Any attempt to explain the emergence of facts (“the emergence of classicality,” as it is sometimes called) must therefore be a wholly gratuitous endeavor.

Classical physics deals with nomologically possible worlds — worlds consistent with physical theory. It does not uniquely determine the actual world. Identifying the actual world among all nomologically possible worlds is strictly a matter of observation. Does this imply that classical physics presupposes conscious observers? Obviously not. In classical physics the actual course of events is in principle fully determined by the actual initial conditions (or the actual initial and final conditions). In quantum physics it also depends on unpredictable actual states of affairs at later (or intermediate) times. Accordingly, picking out the actual world from all nomologically possible worlds requires observation not only of the actual initial conditions (or the actual initial and final conditions) but also of those unpredictable actual states of affairs. Does this imply that quantum physics presupposes conscious observers? If the answer is negative for classical physics, it is equally negative for quantum physics.

The principal trouble with quantum mechanics is “the disaster of objectification,” as the philosopher of science Bas van Fraassen has called it. What is meant by “objectification” is the coming into being of a measurement outcome. The disaster is that quantum mechanics cannot explain how it is that measurements have outcomes. It seems perfectly reasonable to assume that a measurement involves an interaction between a measurement apparatus and a system on which the measurement is performed. Yet if this interaction is modeled as a physical process, and if this process is described in quantum-mechanical terms, what follows is that there is no such thing as a measurement outcome.

It remains true that attempts to explain the coming into being of measurement outcomes in objectivistic terms, through some physical mechanism or natural process, are misconceived and uncalled-for. But it also remains true that identifying the actual world among all nomologically possible worlds is strictly a matter of observation. My mistake was to argue that if classical physics does not presuppose observers, then quantum physics doesn’t either.

If classical physics assigns probability 1 to finding that an observable Q has the value q, it is consistent to assume that the value of Q is q. And if classical physics assigns probability 0, it is consistent to assume that the value of Q is anything but q. The reason is that classical physics (excluding classical statistical physics) only assigns the trivial probabilities 0 or 1. If quantum physics assigns probability 1 to finding that Q has the value q, on the other hand, it is not consistent to assume that the value of Q is q. The reason is that the probabilities that quantum physics serves to assign span the entire gamut between 0 and 1. If quantum mechanics assigns probability 1 to q, it only means that a measurement (if performed) is certain to yield the outcome q. Only if a measurement indicates that Q has the value q, does Q have the value q.

So much for the appetizer. Now for the main course. The point I made in my 2002 paper about the block universe and the flow of time begins with these observations:

We are accustomed to the idea that the redness of a ripe tomato exists in our minds, rather than in the physical world. We find it incomparably more difficult to accept that the same is true of the experiential now: It has no counterpart in the physical world. There simply is no objective way to characterize the present. And since the past and the future are defined relative to the present, they too cannot be defined in objective terms. The temporal modes past, present, and future can be characterized only by how they relate to us as conscious subjects: through memory, through the present-tense immediacy of qualia (introspectable properties like pink or turquoise), or through anticipation. In the world that is accessible to physics we may qualify events or states of affairs as past, present, or future relative to other events or states of affairs, but we cannot speak of the past, the present, or the future.... The idea that some things exist not yet and others exist no longer is as true and as false as the idea that a ripe tomato is red.

The fact that the experiential now cannot be objectivized — that it is absent from both the vocabulary and the world of physics — bothered Einstein to no end. This is from an account given by the philosopher Rudolf Carnap1 of a conversation he had with Einstein:

He explained that the experience of the Now means something special for man, something essentially different from the past and the future, but that this important difference does not and cannot occur within physics. That this experience cannot be grasped by science seemed to him a matter of painful but inevitable resignation.... Einstein thought that ... there is something essential about the Now which is just outside of the realm of science. We both agreed that this was not a question of a defect for which science could be blamed, as Bergson thought. I did not wish to press the point, because I wanted primarily to understand his personal attitude to the problem rather than to clarify the theoretical situation. But I definitely had the impression that Einstein's thinking on this point involved a lack of distinction between experience and [theoretical] knowledge.

When his friend Michele Besso died in March 1955, just weeks before his own death, Einstein ended a letter to members of Besso’s family with the following words: “Now he has again preceded me a little in parting from this strange world. This has no importance. For people like us who believe in physics, the separation between past, present and future has only the importance of an admittedly tenacious illusion.”

Essential to Einstein’s conception of physics is the conception of physical space as a three-dimensional transfinite manifold, which is incompatible with the quantum-mechanical uncertainty principle and the contextuality of the measurable properties of quantum objects, as I have explained in my last post. Einstein’s theory of relativity combines this conception of physical space and an analogous conception of physical time into a four-dimensional transfinite manifold called “spacetime.”

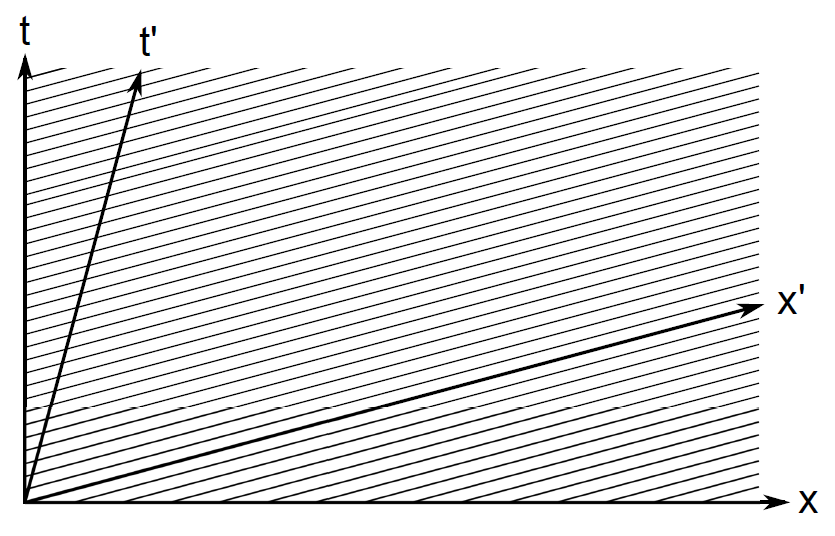

The simplest illustrations of spacetime are two-dimensional; they contain a (usually vertical) time axis, along which time increases upwards, and a single (usually horizontal) space axis. In the diagram above, the axis marked t (as well as any other vertical line) represents the successive positions of a (real or imagined) clock at rest. The axis marked t’ (as well as every straight line parallel to it) represents the successive positions of a clock moving to the right at a constant speed. In Newtonian physics, the points at which the clocks at rest and the moving clocks show the same time are all located on the same horizontal line. Simultaneity therefore is absolute.

Not so in relativistic physics, where not only the two time-axes but also the two space-axes (x and x’) point in different (spacetime) directions. While the points at which the clocks at rest show the same time are again located on the same horizontal line, the points at which the moving clocks show the same time are located on a line that is parallel to the axis x’. Simultaneity therefore depends on whichever reference frame is used to describe the physical situation—F₁ with axes t and x or F₂ with axes t’ and x’.

Reference frames belongs to the language which is used to describe a physical situation. A physical situation described in English is no more English than a physical situation described in French is French. Englishness and Frenchness cannot be objectivized; neither of them can be a physical aspect of the situation described. The same is true of simultaneity. Because it depends on the language we use to describe a physical situation, simultaneity cannot be objectivized; it cannot be a physical aspect of the situation described.

In the philosophy of time, one distinguishes between presentism, possibilism, and eternalism. Presentism holds that only the present is real: the past exists no longer, the future not yet. Possibilism holds that the past is fixed and settled, while the future is open; it is in the process of being created. One may think of it as a tree of branching possibilities, some of which will become actualities. Eternalism, finally, holds that past, present, and future coexist and are equally real; the spatiotemporal whole is thought to exist as a single four-dimensional block — the infamous “block universe.” (The term appears to have been coined by William James.2)

The relativity of simultaneity is widely seen as a refutation of both presentism and possibilism. This seems to leave the block universe as the only viable option. In relativistic spacetime one can find, for any two successive events A and B, two reference frames F₁ and F₂ and a third event C such that C is simultaneous with A in F₁ and simultaneous with B in F₂. This “simultaneity by proxy” of the successive events A with B appears to compel us to conceive of all parts of the spatiotemporal whole as coexistent and equally real.

Eternalism has the obvious implication of fatalism, the view that the future is as fixed and settled as the past; there is nothing one can do about it. To the renowned mathematician and theoretical physicist Herman Weyl3 it meant that the distinctions we make between past, present, and future have no objective reality. Change and becoming are subjective phenomena, confined to the way we experience the world — psychic additions (as Whitehead would describe them) just like the red color of a ripe tomato:

The objective world simply is; it does not happen. Only to the gaze of my consciousness, crawling upward along the life line of my body, does a section of this world come to life as a fleeting image in space which continuously changes in time.

Similarly Arthur Eddington4: “Events do not happen: they are just there, and we come across them.” Likewise Louis de Broglie5: “Each observer, as his time passes, discovers, so to speak, new slices of space-time which appear to him as successive aspects of the material world, though in reality the ensemble of events constituting space-time exist prior to his knowledge of them.”

But wait. Let’s stop to think for a moment. If neither the experiential now nor the distinction between the past, the present, and the future can be objectivized, how can I project my upward-crawling gaze into an objective block universe? Here is another paragraph from my 2002 paper:

If we conceive of temporal relations, we conceive of the corresponding relata simultaneously — they exist at the same time in our minds — even though they happen or obtain at different times in the objective world. Since we can't help it, that has to be OK. But it is definitely not OK if we sneak into our simultaneous spatial mental picture of a spatiotemporal whole anything that advances across this spatiotemporal whole. We cannot mentally represent a spatiotemporal whole as a simultaneous spatial whole and then imagine this simultaneous spatial whole as persisting in time and the present as advancing through it. There is only one time, the fourth dimension of the spatiotemporal whole. There is not another time in which this spatiotemporal whole persists as a spatial whole and in which the present advances, or in which an objective instantaneous state evolves. If the present is anywhere in the spatiotemporal whole, it is trivially and vacuously everywhere — or, rather, everywhen.

In the block universe, there simply is no place for an upward-crawling gaze of consciousness such as Weyl, Eddington, de Broglie and many others imagine. The fact that the distinction between past, present and future cannot be objectivized — that it cannot be smuggled into the block-universe conception of physical reality — does not mean that the distinction is, as Einstein wrote in his letter to Besso’s family, “an admittedly tenacious illusion.” It means that there is something terribly wrong with the block-universe conception of physical reality.

First of all, if all parts of the spatiotemporal whole coexist in some sense, it cannot mean that they exist simultaneously; that would be an egregious contradiction in terms. The coexistence of the spatiotemporal whole can only be a timeless coexistence, and of that our minds can form no adequate conception. In a previous post I quoted a passage by Sri Aurobindo,6 in which he speaks of “a consciousness higher than Mind which should regard our past, present and future in one view, containing and not contained in them, not situated at a particular moment of Time for its point of prospection”:

At certain moments we become aware of such an indivisible regard upholding by its immutable self-conscious unity the variations of the universe. But we must not now ask how the contents of Time and Space would present themselves there in their transcendent truth; for this our mind cannot conceive. (LD 144)

It is imperative that we distinguish between a supramental consciousness, to which the timeless coexistence of the spatiotemporal whole is an aspect of its experience of reality,7 and our mental consciousness. A mentally conscious being is always situated in the present, where it remembers the past and anticipates the future. Such a being would be paralyzed by knowledge of the future. If to me (a mentally conscious being) the future were as accessible as the past, I could know my choices before I made them, and therefore I could not feel as if I made them of my own free will. I could not even conceive of myself as an agent. The reason I can think of myself as an agent is precisely that the future is inaccessible to me, occasional veridical premonitions notwithstanding. And if I can think of myself as an agent, then it is also perfectly possible for future events to be influenced by choices I have made, even freely, in the present or the past.

That I can think of myself as an agent is essential to the Sachchidananda’s adventure of evolution, but it does not imply that my choices are freely made. The evolution of freedom consists in a gradual transition from a wholly illusory freedom to a total and genuine freedom. The transitional stage at which we find ourselves at present is succinctly epitomized by a line in Sri Aurobindo’s epic poem Savitri8:

Nature does most in him, God the high rest.

In more prosaic terms9:

That clear inclination of the mind which we call our will, that firm settling of the inclination which presents itself to us as a deliberate choice, is one of Nature’s most powerful determinants; but it is never independent and sole. Behind this petty instrumental action of the human will there is something vast and powerful and eternal that oversees the trend of the inclination and presses on the turn of the will.

At bottom, there is only one way that complete freedom is possible: to be the sole determinant of all that happens or is the case in the world. The goal of evolution is to become consciously identified with this sole determinant, and therefore to become completely free. According to Sri Aurobindo, one aspect of “the goal of Nature in her terrestrial evolution” is “to establish an infinite freedom in a world which presents itself as a group of mechanical necessities” (LD 4). To a supramentally conscious being, its comprehensive vision of past, present, and future (trikāladṛṣṭi) is not an impediment but rather a precondition for its infinite freedom. Real knowledge and real freedom go hand in hand. The more limited is our knowledge, the more limited will be our freedom. Conversely, total knowledge (which is necessarily a supramental knowledge) implies total freedom.

In my last post I argued that if (in our minds) we keep cutting up physical space into ever smaller regions, we will reach a point where the distinctions we make between regions cease to correspond to anything in the physical world, a point where such distinctions can no longer be objectivized. The same argument can be made for time, with the implication that there can be no such thing as an instantaneous physical state, inasmuch as this would require an intrinsically and completely differentiated time. So there are two arguments against the importation of an evolving instantaneous state into the block universe: the spatiotemporal whole has room neither for an evolving state nor for an instantaneous state.

One implication of the passage from my 2002 paper quoted first in this missive is that we must distinguish between facts (actual events and states of affairs) and the laws that codify the correlations between facts — the statistical correlations of quantum physics and the deterministic ones of classical physics.

As to the facts, they are facts because they are experienced by us and/or because they can be objectivized — we can think of them as elements of a reality shared by us. The passing or flow of time and the quality of spatial extension are aspects of this shared reality.

As to the physical laws, in order to formulate them we need a spacetime geometry, i.e., a set of instructions for measuring distances and durations. The special theory of relativity is such a set. It is customary to illustrate the salient features of the relativistic interlinking of distances and durations with the help of spacetime diagrams. Among these features are the relativity of simultaneity, the shortening of moving rods, the slowing down of moving clocks, the invariance of the speed of light, and the famous formula for converting mass units into energy units, E=mc². It is also customary to refer to the points in spacetime diagrams as “events,” but since spacetime diagrams contain no trace of the experiential flow of time, it is of utmost importance that we do not conflate these so-called events with the actual events we experience and are able to objectivize. The metaphysical quagmire associated with the block-universe results from this mindless conflation.

R. Carnap, Intellectual autobiography, in: P.A. Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap, pp. 37–38 (Open Court, 1963).

W. James, A Pluralistic Universe, p. 76 (Longmans, Green, and Co., 1920). POSTSCRIPT: Chris Fuchs has found an earlier mention of “block universe” in “The Dilemma of Determinism,” a 1884 lecture by James (Writings 1878–1899, pp. 566–594, The Library of America, 1992).

H. Weyl, Philosophy of Mathematics and Natural Science, p. 116 (Princeton University Press, 1949).

A.S. Eddington, Space, Time and Gravitation (Cambridge University Press, 1920).

L. de Broglie in P.A. Schlipp (ed.), Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, pp. 107–128 (Harper & Row, 1959).

LD = Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2005)

“We are already what we become. That which is still future in matter, is already present in Spirit. That which the mind in matter does not yet know, it is hiding from itself—that in us which is behind mind & informs it already knows—but it keeps its secret.” (Sri Aurobindo, Kena and other Upanishads, p. 299, Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2001)

Sri Aurobindo, Savitri: a Legend and a Symbol, p. 542 (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1997).

Sri Aurobindo, The Synthesis of Yoga, p. 97 (Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1997).

“If you imagine a change as really composed of states, you at once cause insoluble metaphysical problems to arise. They deal only with appearances. You have closed your eyes to true reality” (HB, “The Perception of Change”, Second Lecture)

Bertrand Russell thought that Bergson needed to rely on the concept of duration to avoid falling into the “block universe” trap of mechanism or even teleology (BR, “A History of Western Philosophy”, p. 828). The truth of the matter is that he carefully ignored what Bergson meant at heart, and focused instead on what he said in good style. He didn’t mean to imply that movement can be decomposed into “motions” and “immobilities”, but that we should not attribute to the unity of movement the (dubious) divisibility of space, which is a perfectly valid point. And it was a valid point even before QM. (HB, “The Idea of Duration”, p. 79)

In any case, Russell was right in saying that the ultimate argument for Bergsonism (or for any organic philosophy for that matter) is whether it should appeal to us or not. And we would reply that yes, it lies closer to the idea we have of the living. At which point the reductionist might ask whether it is infinitesimally close, or only asymptotically.. (They always try to get out of a quagmire by pulling their own bootstraps, like Munchausen, a spectacle worth watching).

The discussion at this level is spurious, a different standpoint is needed to approach the “experiential now” of life, which is not within the reach of conceptual analysis. Russell didn’t think that was something philosophy should be concerned with in 1912. Einstein did not see this either after his personal encounter with Bergson, but he could feel it experientially, I’m tempted to guess, perhaps not less as an amateur musician. Nishida understood it better than both in October 1910: “Saggiare nella pratica un concetto [e.g the concept of number] significa chiederci che cosa tramite esso possiamo fare. Dato che il concetto è un simbolo irrigidito e astratto ottenuto in vista di un tale fine, finché lo si usa praticamente non ci sono problemi, ma quando lo si impiega per scopi puramente conoscitivi e si cerca tramite esso di cogliere la realtà concreta in cui si è agito, si cade in errore.” (“Pensiero ed Esperienza Vissuta Corporea”, p.122, Il metodo della filosofia di Bergson).

There is in concrete phenomena (including that of consciousness) a certain depth, a thickness, which remains untouched by the flat mirror of physical law. It is like one of those carefully delineated paintings of Duccio. When presented as a gift to the Pope we might say: It has all been taken care of Your Holiness, we just apologise the artist was unable to fit the Lady and the Child in the centre of the image. It is about high time we place the Madonna and Child in the centre of the image.